Intro

The world is full of complications and interconnections that can only be explained through an understanding of multiple models. Developing a multidisciplinary mindset helps see a problem more accurately and avoid having blind spots. You’re only as good as your tools.

Mental models do two things

• They help you assess how systems work

• They help you make better decisions

A “system” is anything with multiple parts that depend on each other. Every machine and process is a system.

Everyday decisions fall into two categories

➊ Prioritising — which path is the best to take?

➋ Allocating — how much attention, time, or capital should be spent on this?

I believe in the discipline of mastering the best of what other people have figured out.

Charlie Munger

Vol I : General Thinking Concepts

The Map

- The map is not the territory. The description of the thing is not the thing itself. The model is not reality. The abstraction is not the abstracted

- A map can also be a snapshot of a point in time, represeting something that no longer exists

- Maps simplify some complex territory in order to guide you through it

eg. financial statement, policy document, manual, GPS - They’re useful to the extend that they’re explantory & predictive

- The only way we can navigate the complexity of reality is through some sort of abstraction. We can lose the specific and relevant details that were distilled into an abstraction

- We often consume these abstractions as gospel, without having done the hard mental work ourselves, it’s tricky to see when the map no longer agrees with the territory

- Maps have its limitations. We must realise that we do not understand a model, map, or reduction unless we understand and respect its limitations

- Maps are static references to the dynamic world

Remember that all models are wrong; the practical question is how wrong do they have to be to not be useful.

George Box

- In order to use a map or model as accurately as possible, we should take three important considerations into account:

- Reality is the ultimate update: update the maps based on our own experiences in the territory

- Consider the cartographer: maps are not purely objective creations. They reflect the values, standards, limitations and intentions of their creators

- Maps can influence territories

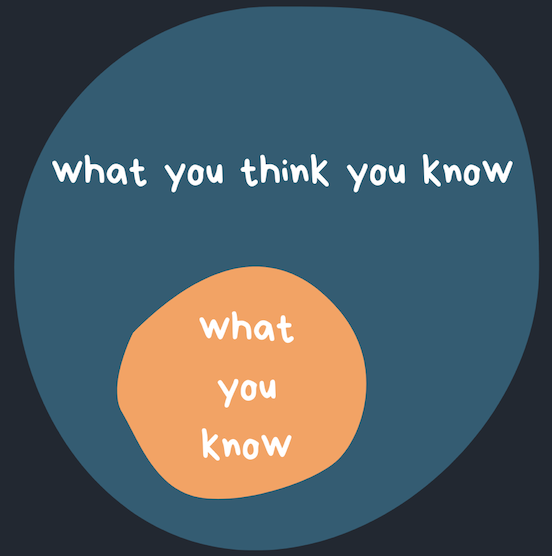

Circle of Competence

- Circle of competence is the detailed web of knowledge

- 3 key practices to build and maintain a circle of competence

➊ curiosity & a desire to learn

➋ monitoring

➌ feedback (both internal & external) - Learning comes when experience meets reflection. You can learn from your own experiences or you experience of others. The latter is much more productive

- Monitor your track record in areas which you have, or want to have, a circle of competence

- Keeping a journal of your own performance is the easiest and most private way to give self-feedback. Journals allow you to step out of your automatic thinking and ask yourself: What went wrong? How could I do better?

- Monitoring your own performance allows you to see patterns that you simply couldn’t see before. This type of analysis is painful for the ego, which is also why it helps build a circle of competence. You can’t improve if you don’t know what you’re doing wrong

- 3 parts to successfully operating outside a circle of competence:

➊ learn the basic of the realm you’re operating in

➋ seek expertise

➌ use broad understanding of the basic mental models - Incentives can really skew how much you can realy on someone else’ circle of competence. (Don’t automatically trust people who have something at stake from your decision – from Seeking Wisdom)

Falsifiability

- If you can’t prove something wrong, you can’t really prove it right either

- Falsification is the opposite of verification; you must try to show the theory is incorrect, and if you fail to do so, you actually strengthen it

First Principles Thinking

- First principles thinking identifies the elements that are non- reducible. It’s not necessarily looking for absolute truths

- Everything that is not a law of nature is just a shared belief eg money, border, bitcoin, love

- 2 techniques we can use to cut through the dogma and shared belief

➊ scratic questioning

➋ five whys - Scratic questioning draws out first principles in a systematic manner. here is the process

- Clarifying your thinking and explaining the origins of your ideas. (Why do I think this? What exactly do I think?)

- Challenging assumptions. (How do I know this is true? What if I thought the opposite?)

- Looking for evidence. (How can I back this up? What are the sources?)

- Considering alternative perspectives. (What might others think? How do I know I am correct?)

- Examining consequences and implications. (What if I am wrong? What are the consequences if I am?)

- Questioning the original questions. (Why did I think that? Was I correct? What conclusions can I draw from the reasoning process?)

- The goal of the five whys is to land on a “what” or “how”. It is not about introspection, such as “Why do I feel like this?” Rather, it is about systematically delving further into a statement or concept so that you can separate reliable knowledge from assumption. If your “whys” result in a statement of falsifiable fact, you have hit a first principle

Science is much more than a body of knowledge. It is a way of thinking.

Carl Sagan

Thought Experiment

- Thought experiments can be defined as “devices of the imagination used to investigate the nature of things”

- Typical steps of a thought experiment

➊ ask a question

➋ conduct background research

➌ construct hypothesis

➍ test with (thought) experiments

➎ analyze outcomes and draw conclusions

➏ compare to hypothesis and adjust accordingly - Areas in which thought experiments are tremendously useful

➊ imagining physical impossibilities

➋ re-imagining history

➌ intuiting the non-intuitive - When we say “if money were no object” or “if you had all the time in the world,” we are asking someone to conduct a thought experiment because actually removing that variable is physically impossible

- If Y happened instead of X, what would the outcome have been? Would the outcome have been the same? These approaches are called the historical counter-factual and semi- factual

- Thought experiments improves our ability to intuit the non-intuitive. A thought experiment allows us to verify if our natural intuition is correct by running experiments in our deliberate, conscious minds that make a point clear

- Thought experiments are often used to explore ethical and moral issues

- Thought experiments tell you about the limits of what you know and the limits of what you should attempt

Necessity & Sufficiency

- We often make the mistake of assuming that having some necessary conditions in place means that we have all of the sufficient conditions in place for our desired event or effect to occur

- The gap between what is necessary to succeed and what is sufficient is often luck, chance, or some other factor beyond your direct control

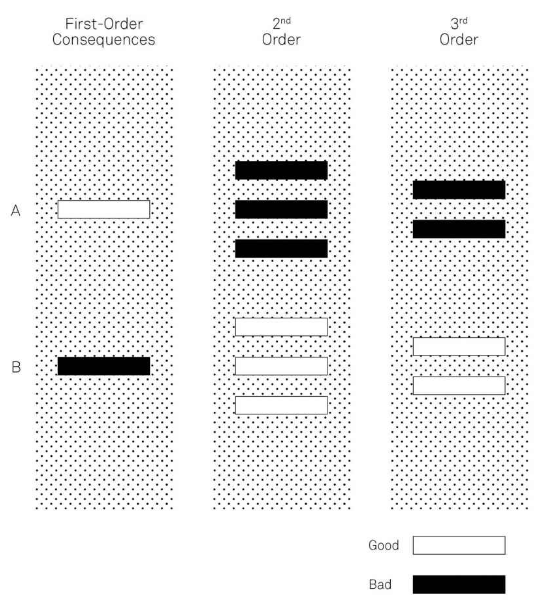

Second Order Thinking

- Second order thinking is about the consequences of consequences

- It requires us to not only consider our actions and their immediate consequences, but the subsequent effects of those actions as well

- Failing to consider the second- and third-order effects can cause unintended consequences eg cobra effect ( perverse incentive)

- Areas where second-order thinking can be used to great benefits

➊ prioritising long-term interests over immediate gains

➋ constructing effective arguments - Engage in second-order thinking to scrutinise your decisions & bolster your arguments

Probabilistic Thinking

- Use probabilistic thinking to weight your decisions more precisely

- 3 important aspects of probability

➊ bayesian thinking

➋ fat-tailed curves

➌ asymmetries (skewness) - Bayes’ theorem describes how to update the probabilities of hypotheses when given evidence

- Conditional probability is the probability of one event given that another event occurred (a fixed value). It is the base concept in Bayes theorem

- Bayesian thinking means when we encounter new info, we should take into account relevant prior knowledge, before we make a decision or reach a conclusion

- For each bit of prior knowledge, you are not putting it in a binary structure (true/false). You’re assigning it a probability of being true — bayes factor (likelihood ratio). Any new info you encounter that challenges a prior simply means that the probability of that prior being true may be reduced

- When making uncertain decisions, ask: What are the relevant priors? What might I already know that I can use to better understand the reality of the situation?

- Fat-tailed distributions are graphical representations of the probability of extreme events being higher than normal eg wealth, marketing

Inversion

- 2 approaches to applying inversion

- start by assuming that what you’re trying to prove is either true or false, then show what else would have to be true

- think deeply about what you want to avoid and then see what options are left over

Occam’s Razor (opt for simplicity)

- Occam’s Razor is a general rule by which we select among competing explanations. We should prefer the simplest explanation (fewest variables). They are easier to falsify, easier to understand, and generally more likely to be correct

- Simplicity can incrase efficiency

Hanlon’s Razor (stupidity > evil intent)

- “Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity” If you can explain it as stupid, don’t explain it as malicious

- It’s better to assume that negative outcomes occurred as a result of stupidity or similar causes (eg laziness, ignorance, carelessness, incompetence, or lack of information), rather than bad intentions (eg malice or self-interest)

- Hanlon’s Razor demands that we ask if there is another reasonable explanation for the events that have occurred. The explanation most likely to be right is the one that contains the least amount of intent

- Hanlon’s Razor helps us avoid paranoia and negative emotions