Summary of the Blinkist summary :

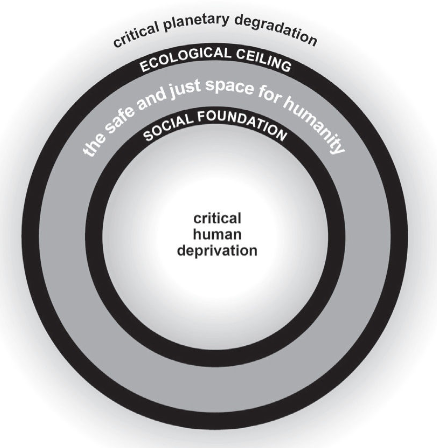

The doughnut

The doughnut is a new way of thinking about sustainable economics in the 21st century. The outside edge of a doughnut is the “ecological ceiling“, while the inside edge is the “social foundation“. Between these two rings is “a safe and just home for humanity.” A place defined by dynamic balance. Within it, all our social needs can be met without overburdening the planet.

① Social foundation

It includes everything that humans need in order to live. That covers basics such as access to clean water and food, but there’s more to it than survival. We want to thrive. Human life requires more abstract social goods like support networks, a sense of community, political representation and gender equality.

② Ecological ceiling

The ecological boundary we have to respect if we also want the earth to thrive. It functions as a “guardrail” to protect the key processes vital to our planet’s ability to sustain human life. If we cross it, we risk environmental catastrophe. And we’ve already leapt over the rail with stuff like climate change.

Economics is not just about the market

A classic economic model often used to explain the world is the circular flow diagram. It pictures the economy as a closed system in which income flows between businesses and households – with banks, governments and trade playing intermediary roles. It’s a powerful image that continues to shape the way we think about the economy. There’s just one catch – it’s wrong! However powerful the market is, it isn’t the only economic sector that creates value.

There’s another flaw in the circular flow model: The economy isn’t a truly closed system. All economic activity depends on the resources provided by the sun and our own planet. The economy is an open subsystem of the earth’s closed system. Without the energy and raw materials we get from the sun and the earth, economic life would grind to a halt. When we take more from the earth than it gives us and expect it to absorb more waste than it can handle, we find ourselves in a “full world.”

Flawed assumptions about human behaviour

Economic Man is a theoretical person who acts rationally, has perfect knowledge and seeks to maximise utility. The presence of an economic man is an assumption of many economic models. In reality, people’s behaviour isn’t anywhere near as uniform as the model suggests. Economics often rests on flawed and mistaken assumptions about human behaviour. Modern economics needs to align itself with how people actually behave in real life.

The real-world economy is a complex network of an interrelated system

The models used by economists are over-simplified. Ironing out the messy reality of the world means making simplistic assumptions that don’t mirror the way things actually work. Economic Man is one of those assumptions and that’s dangerous because it overlooks the unpredictable boom-and-bust cycles of the market.

Take the 2008 financial crisis. Because mainstream economists were convinced that markets naturally stabilise themselves, they overlooked the warning signs. They ignored the banking sector and failed to analyse its unique complexities and vulnerabilities. The Fed Reserve didn’t even include private banks in its models. When the crash came, they were caught out.

Economics in the 21st-century needs to change so as to avoid future disasters. That means dropping mechanical metaphors and thinking about economies as massive systems of interconnected variables. Equilibrium isn’t likely in these kinds of systems. Instead, individual components interact, reinforcing one another like feedback loops. It enables us to monitor the complex interactions of an economy, and that’s a much better approach than blind faith in the market’s ability to balance itself.

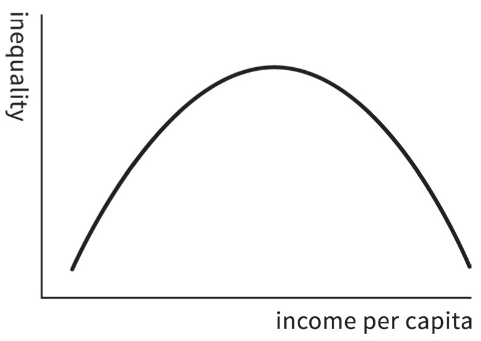

Inequality isn’t a precondition of economic growth

The Kuznets Curve implies that economic growth worsens income inequality first, once a nation has better economic development (reaches the local maximum), inequality decreases. However, this model is deeply flawed. The data suggests otherwise: high-income countries are experiencing the highest levels of inequality in 30 years.

Rising incomes alone can’t make societies more equal, but a better design can.

The Bangla-Pesa wasn’t a replacement for the national currency, the Kenyan shilling, but a slum currency. The idea was that it’d be used to buy and sell goods within the local area in which money often scarce. It let people save their shillings for utilities which have to be paid for in cash.

Review :

Blinkist | Amazon | Good Reads