Review: Packing for Mars is not about Mars but rather the science of human beings living in space. A lot of our day to day routine doesn’t seem to be a big deal until you hit space like breathing, eating, pooping etc. things we take for granted. It’s fascinating how scientists overcome all those challenges.

Roach’s writing style makes this information-dense book a page-turner. It’s witty and hilarious. And she didn’t just summarise those scientific findings but translated them to layman terms. I enjoyed reading it immensely. Highly recommended.

Some of my favourite passages

People can’t anticipate how much they’ll miss the natural world until they are deprived of it. […]

Ch 2 Life in a Box

On a Mars mission, once astronauts lose sight of Earth, there’ll be nothing to see outside the window. “You’ll be bathed in permanent sunlight, so you won’t even see any stars,” astronaut Andy Thomas explained to me. “All you’ll see is black.”

Humans don’t belong in space. Everything about us evolved for life on Earth. Weightlessness is an exhilarating novelty, but floaters soon begin to dream of walking. Earlier Laveikin told us, “Only in space do you understand what incredible happiness it is just to walk. To walk on Earth.”

Packing for Mars by Mary Roach

Along with electromagnetism and strong and weak nuclear forces, gravity is one of the “fundamental forces” that power the universe. It was reasonable to assume that gravity might have something darker up its sleeve that mankind was yet unaware of. […]

Ch 4 The Alarming Prospect of Life Without Gravity

Gravity is the pull, measurable* and predictable, that one mass exerts on another. The more mass involved, and the shorter the distance between the masses, the stronger the pull. […]

Gravity is why there are suns and planets in the first place. It is practically God […]

Gravity is the prime reason there’s life on Earth. Yes, you need water for life, but without gravity, water wouldn’t hang around. Nor would air. It is Earth’s gravity that holds the gas molecules of our atmosphere—which we need not only to breathe but to be protected from solar radiation—in place around the planet. Without gravity, the molecules would fly off into space along with the water in the oceans and the cars on the roads and you and me and Larry King and the dumpster in the In-N-Out Burger parking lot.

Packing for Mars by Mary Roach

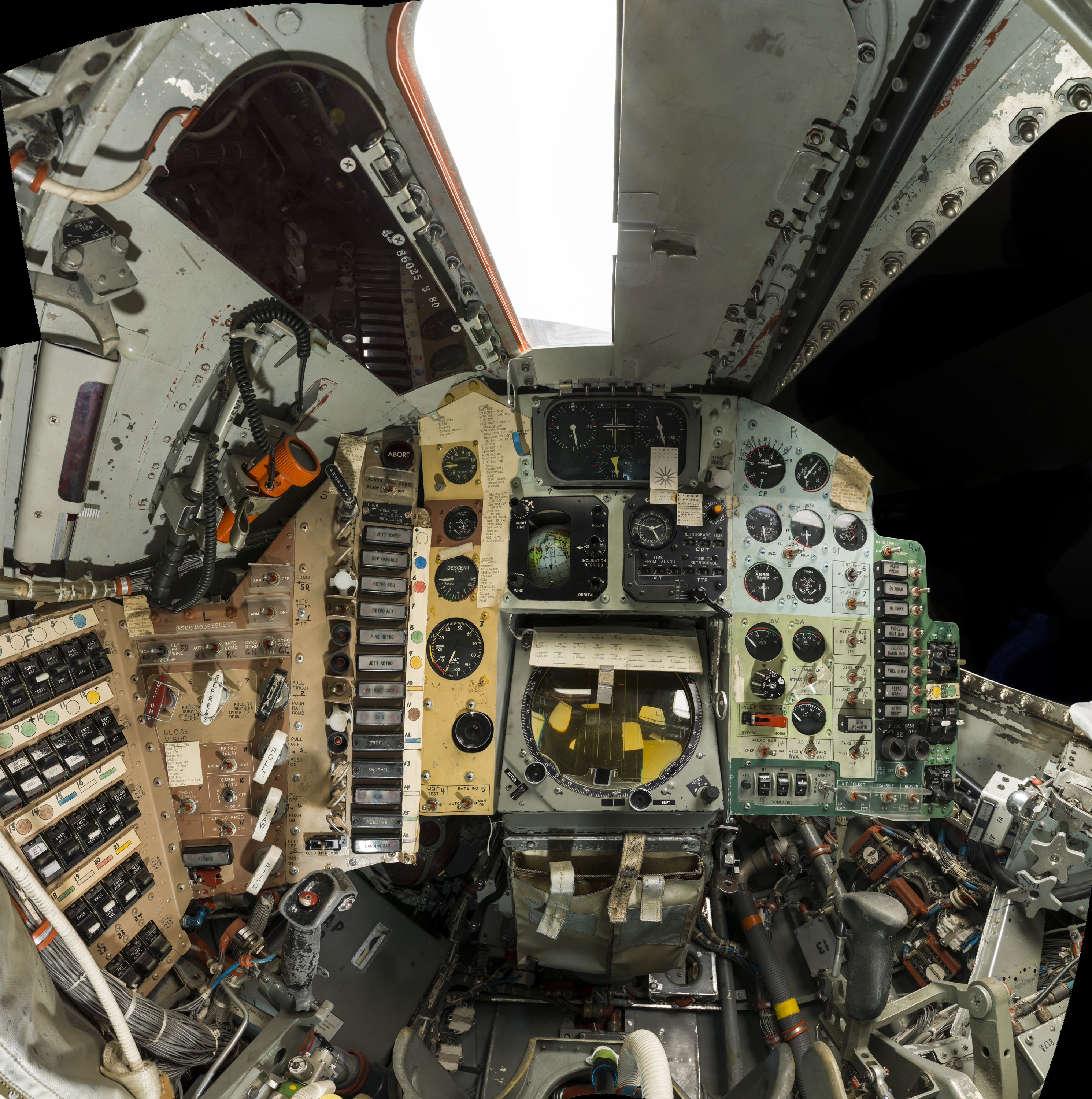

Nothing works as it’s supposed to in zero gravity, or zero G, as it’s also known. “Even something as simple as a fuse,” astronaut Chris Hadfield told me, mistaking me for someone who knows how a fuse works. Now I know: Fuses have a metal strip that melts in response to a surplus of current. The molten bit drips away, leaving a gap that interrupts the power flow. Without gravity, the droplet doesn’t drip, so the power continues to flow until the metal boils, by which time the equipment has fried. Zero gravity is part of the reason NASA price tags seem so extravagant. For every new piece of equipment that goes up on a mission—every pump, fan, throttle, widget—a prototype must be flown on the C-9 to be sure it works in weightlessness.

Ch 5 Unstowed

Packing for Mars by Mary Roach

Astronauts have to deal with the mother of all sensory conflicts: the visual reorientation illusion. This is where up, without warning, becomes down. […] It happens most readily in spaces with no obvious visual clues as to which is the floor and which the ceiling or wall

Ch 6 Throwing Up and Down

Drugs help keep astronauts out of bed, moving and going about their work. But they also confer a false sense of immunity, encouraging one to overdo it. Motion sickness drugs don’t make you immune; they simply raise the threshold for sickness.

Packing for Mars by Mary Roach

In a space capsule, every landing is something of a crash landing. Unlike a plane or the Space Shuttle, a capsule has no wings or landing gear. It doesn’t fly back from space; it falls. […] Crashes often involve forces along not just one axis, but two or three of them. […]

Ch 7 The Cadaver in the Space Capsule

Safeguarding a human for a multiaxis crash is not all that different from packing a vase for shipping. Since you don’t know which side the UPS guy’s going to drop it on, you need to stabilize it all around.

Packing for Mars by Mary Roach

Apollo astronauts had to be between 5 feet 5 and 5 feet 10. It was a simple, inflexible cutoff, the governmental version of the sign by the amusement park ride: MUST BE THIS TALL TO RIDE.

Ch 7 The Cadaver in the Space Capsule

Packing for Mars by Mary Roach

“Many ophthalmologists thought the eye would change its shape and that this would change the vision, so that maybe the man in space would not be able to see at all.” That is why, if you’d looked inside Glenn’s capsule, you’d have seen a scaled-down version of the classic Snellen eye chart taped to the instrument panel. Glenn had been given instructions to read the chart every twenty minutes. A color blindness test and a device to measure astigmatism were also on board. I used to hear about Glenn’s historic flight and think, “Man, what was that like—being the first NASA astronaut to orbit the Earth?” Now I know. It was like visiting the eye doctor.

Ch 8 One Furry Step for Mankind

Packing for Mars by Mary Roach

Timing is critical to an astronaut wandering around on an extraterrestrial surface. Without knowing how long it takes to walk or drive a given distance on a certain kind of terrain, it’s hard to know how much oxygen or battery life one will need. Apollo astronauts had to conform to “walkback constraints.” […]

Ch 9 Next Gas: 200,000 Miles

Apollo astronauts were not allowed to drive farther from the safety of the Lunar Module than the distance they could walk without running out of oxygen, in case the rover broke down.

Packing for Mars by Mary Roach

NASA WILL PAY YOU TO LIE IN BED

Ch 11 The Horizontal Stuff

For three months, twenty-four hours a day, Leon does not get up—or even sit up—for anything: not to shower, not to eat, not to use the toilet. Bed rest is an analog, or mimic, of spaceflight in that staying off one’s feet causes the same sorts of bodily degradations that weightlessness causes. Most direly, the bones thin and the muscles atrophy. Space agencies study bed-resters to try to understand these changes and figure out how best to counteract them.

Packing for Mars by Mary Roach

As on Earth, weight-bearing exercise is the best way to hang on to your bone. In zero gravity, of course, you have to create your weight. The problematic and expensive way to do this is to outfit the space station with a rotating room, a huge, inhabitable centrifuge that spins astronauts outward toward the walls, creating artificial gravity. (Keir Dullea can been seen jogging on one in 2001: A Space Odyssey.) The funky and affordable alternative is to mimic weight by pulling astronauts’ bodies down into a treadmill belt as they jog. Typically this involves a harness and bungee cords and much cursing and chafing. It is not tremendously effective. Bone loss researcher Tom Lang says this kind of device pulls exercisers against the belt with about 70 percent of their bodyweight, a scenario that still translates to “massive bone loss.”

Ch 11 The Horizontal Stuff

Packing for Mars by Mary Roach

Back in the 1980s, some clandestine experiments were conducted very late at night in the neutral buoyancy weightless simulation tank at NASA’s George C. Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. The experimental results showed that yes, it is indeed possible for humans to copulate in weightlessness. However, they have trouble staying together. The covert researchers discovered that it helped to have a third person to push at the right time in the right place. The anonymous researchers…discovered that this is the way dolphins do it. A third dolphin is always present during the mating process. This led to the creation of the space-going equivalent of aviation’s Mile High Club known as the Three Dolphin Club.

Ch 12 The Three Dolphin Club

Packing for Mars by Mary Roach

NASA doesn’t specifically address sex in its rules of conduct. Its Astronaut Code of Professional Responsibility includes a vague Boy Scout Oath–style pledge, “We will strive to avoid the appearance of impropriety.” To me, that just means, Don’t get caught.

Ch 12 The Three Dolphin Club

Packing for Mars by Mary Roach

The Johnson Space Center “potty cam,” as it is more casually known, is an astronaut training aid. It provides a vivid, arresting perspective on something you’ve had intimate contact with all your life but never really seen. […] Positioning is critical because the opening to a Space Shuttle toilet is 4 inches across, as opposed to the 18-inch maw we are accustomed to on Earth.

Ch 14 Separation Anxiety

Packing for Mars by Mary Roach

:format(webp):no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/15978228/moon_poop_BAG.jpg)

The fecal bag is a clear plastic sack, similar to a vomit bag in its size, holding capacity, and ability to inspire dread and revulsion. A molded adhesive ring at the top of the bag was designed for the average curvature of an astronaut’s cheeks. It rarely fit. The adhesive pulled hairs. Worse, without gravity or air flow or anything else to foster separation, the astronaut was obliged to employ his finger. Each bag had a small inset pocket near the top, called a “finger cot.”

Ch 14 Separation Anxiety

The fun didn’t stop there. Before he could roll up and seal the bag to trap the offending monster, the crew member was further burdened with tearing open a small packet of germicide, squeezing the contents into the bag, and manually kneading the germicide through the feces. Failure to do so would allow fecal bacteria to do their bacterial thing, digesting the waste and expelling the gas that, inside your gut, would become your own gas. Since a sealed plastic fecal bag cannot fart, it could, without the germicide, eventually burst

Packing for Mars by Mary Roach

The new imperative at NASA was to develop food that was not only lightweight and compact, but also “low-residue.” […]

Ch 15 Discomfort Food

IRONICALLY, IF YOU wanted to minimize an astronaut’s “residue,” you could have fed him exactly what he wanted: a steak. Animal protein and fat have the highest digestibility of any foods on Earth. The better the cut, the more thoroughly the meat is digested and absorbed—to the point where there’s almost nothing to egest (opposite of ingest). […]

That’s one reason NASA’s traditional launch day breakfast is steak and eggs.† An astronaut may be lying on his back, fully suited, for eight hours or more. You do not want to be eating Fiber One the morning before liftoff. (The Soviet space agency did not traditionally give cosmonauts steak and eggs before launch; it gave them a one- liter enema.)

Packing for Mars by Mary Roach

With the 2010 publication of Charles Bourland’s incomparable Astronaut’s Cookbook, it is now possible to whip up eighty-five high-fidelity shuttle-era entrées and sides in your own kitchen, should your own kitchen happen to contain “National 150 filling starch aid from National Starch and Chemical Company” and “caramelized garlic base #99-404 from Eatem Foods.”

Ch 15 Discomfort Food

Packing for Mars by Mary Roach

To serve beef to two or three Mars astronauts, “a steer of 500-kilogram body weight has to be hauled into space.” Whereas the same number of calories could be derived from just 42 kilograms of mice (about 1,700 of them). “The astronauts,” stated the paper’s conclusion, “should eat mouse stew instead of beef steaks.”

Ch 16 Is Mars Worth It?

Packing for Mars by Mary Roach

“Food may be processed by many of the same techniques that are used to fabricate structures and shapes from plastic.” Worf did not limit this thinking to food containers but included spacecraft structures normally jettisoned or left behind when preparing to return home.

Ch 16 Is Mars Worth It?

In other words, instead of abandoning the Lunar Module on the moon, the Apollo 11 crew could have broken off pieces to take along and eat on the way home. Thereby needing to carry less food in the first place. Worf envisioned a return-trip menu that included Fuel Tank, Rocket Motor, and Instrument Casing. Leave room for dessert! “Transparent sugar castings as a substitute for windows” also made Worf’s idea list.

[…]

“If the imagination is allowed to wander”—and with D.L. Worf it surely should be—astronauts could also eat their dirty clothes. Worf estimated that “a space crew of four men will, for a 90-day flight regime, dispose of approximately 120 pounds of clothing, if laundry facilities are not available.” For a three-year Mars mission, that’s 1,440 pounds of dirty wash/victuals. Worf reported that several companies were already spinning textiles from soybeans and milk proteins and that the U.S. Department of Agriculture has “prepared [textile] fibers from egg whites and chicken feathers that would be highly acceptable as food under the controlled environment of a spacecraft.” Meaning, I think, that a man who is willing to dine on used clothing is a man unlikely to balk at chicken feathers.

Packing for Mars by Mary Roach

Pretty much any amino acid arrangement can be hydrolyzed. […]

Ch 16 Is Mars Worth It?

“Shoot, what we could do is hydrolyze the stuff back to carbon and make patties out of it.”

“We are not eating shit burgers on the way back.”

Packing for Mars by Mary Roach

A better way to recycle astronautical by-product would be to seal it into plastic tiles and use it as shielding against cosmic radiation. Hydrocarbons are good for this. Metal spacecraft hulls are not; radiation particles break down into secondary particles as they pass through. These fragmented bits can be more dangerous than the intact primary particles. So what if you’d be, as Gerba crowed, “flying in shit!” Beats leukemia.

Ch 16 Is Mars Worth It?

Packing for Mars by Mary Roach

One of the things I love about manned space exploration is that it forces people to unlace certain notions of what is and isn’t acceptable. And possible. It’s amazing what sometimes gets accomplished via an initially jarring but ultimately harmless shift in thinking

Ch 16 Is Mars Worth It?

Packing for Mars by Mary Roach

The tougher question is not “Is Mars possible?” but “Is Mars worth it?”

Ch 16 Is Mars Worth It?

[…]

I see a backhanded nobility in excessive, impractical outlays of cash prompted by nothing loftier than a species joining hands and saying “I bet we can do this.” Yes, the money could be better spent on Earth. But would it? Since when has money saved by government red-lining been spent on education and cancer research? It is always squandered. Let’s squander some on Mars. Let’s go out and play.

Packing for Mars by Mary Roach

◃ Back

Pingback: Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers – ihaveulcers

Comments are closed.