–

Review: Stiff was the second book I’ve read by Mary Roach and damn it was gobsmackingly amazing. Packing for Mars was first (my review here). I thoroughly enjoyed this, but have to admit that I liked Packing for Mars better.

Roach tells compelling stories about dead bodies like human decomposition, human cannibalism, human composting, head transplants etc. A rather graphic read with a healthy dose of humour to take the edge off. It also gives you food for thought like what to do with your body when you’re gone.

Again, Roach is exceptionally skilled at writing technical stuff in a hysterically funny way. Would definitely recommend it.

Some of my fave excerpts

The human head is of the same approximate size and weight as a roaster chicken. I have never before had occasion to make the comparison, for never before today have I seen a head in a roasting pan. But here are forty of them, one per pan, resting faceup on what looks to be a small pet-food bowl. The heads are for plastic surgeons, two per head, to practice on.

Ch 1: A Head is a Terrible Thing to Waste

The heads have been put in roasting pans—which are of the disposable aluminum variety—for the same reason chickens are put in roasting pans: to catch the drippings. […] Skin hooks and retractors are set out with the pleasing precision of restaurant cutlery.

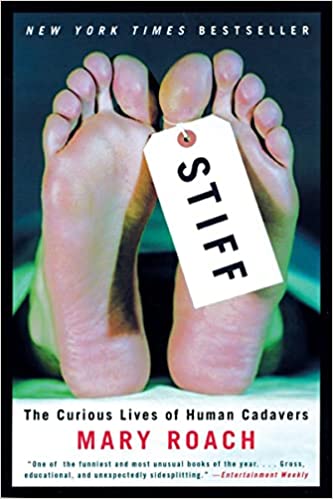

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

The body, it turns out, had been a lodger at a boardinghouse run by Hare and his wife, in an Edinburgh slum called Tanner’s Close. The man died in one of Hare’s beds, and, being dead, was unable to come up with the money he owed for the nights he’d stayed. Hare wasn’t one to forgive a debt, so he came up with what he thought to be a fair solution: He and Burke would haul the body to one of those anatomists they’d heard about over at Surgeons’ Square. There they would sell it, kindly giving the lodger the opportunity, in death, to pay off what he’d neglected to in life.

Ch 2: Life After Death

When Burke and Hare found out how much money could be made selling corpses, they set about creating some of their own. Several weeks later, a down-and-out alcoholic took ill with fever while staying at Hare’s flophouse. Figuring the man to be well on his way to cadaverdom anyway, the men decided to speed things along. Hare pressed a pillow to the man’s face while Burke laid his considerable body weight on top of him. Knox asked no questions and encouraged the men to come back soon. And they did, some fifteen times. The pair were either too ignorant to realize that the same money could be made digging up graves of the already dead or too lazy to undertake it.

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

A series of modern-day Burke-and-Hare-type killings took place barely ten years ago, in Barranquilla, Colombia. The case centred on a garbage scavenger named Oscar Rafael Hernandez, who in March 1992 survived an attempt to murder him and sell his corpse to the local medical school as an anatomy lab specimen. Like most of Colombia, Barranquilla lacked an organised recycling program, and hundreds of the city’s destitute forge a living picking through garbage dumps for recyclables to sell. So scorned are these people that they—along with other social outcasts such as prostitutes and street urchins—are referred to as “disposables” and have often been murdered by right-wing “social cleansing” squads. As the story goes, guards from Universidad Libre had asked Hernandez if he wanted to come to the campus to collect some garbage, and then bludgeoned him over the head when he arrived. A Los Angeles Times account of the case has Hernandez awakening in a vat of formaldehyde alongside thirty corpses, a colorful if questionable detail omitted from other descriptions of the case. Either way, Hernandez came to and escaped to tell his tale.

Ch 2: Life After Death

Activist Juan Pablo Ordoñez investigated the case and claims that Hernandez was one of at least fourteen Barranquilla indigents murdered for medicine—even though an organized willed body program existed. According to Ordoñez’s report, the national police had been unloading bodies gleaned from their own, in-house “social cleansing” activities and collecting $150 per corpse from the university coffers.

[…]

It was around this time that Parliament conceded that the anatomy problem had gotten a tad out of hand and convened a committee to brainstorm solutions. While the debate mainly focused on alternate sources of bodies—most notably, unclaimed corpses from hospitals, prisons, and workhouses— some physicians raised an interesting item of debate: Is human dissection really necessary? Can’t anatomy be learned from models, drawings, preserved prosections?

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

But gross anatomy lab is not just about learning anatomy. It is about confronting death. Gross anatomy provides the medical student with what is very often his or her first exposure to a dead body; as such, it has long been considered a vital, necessary step in the doctor’s education. But what was learned, up until quite recently, was not respect and sensitivity, but the opposite. The traditional gross anatomy lab represented a sort of sink-or-swim mentality about dealing with death. To cope with what was being asked of them, medical students had to find ways to desensitize themselves. They quickly learned to objectify cadavers, to think of the dead as structures and tissues, and not a former human being. Humor—at the cadaver’s expense—was tolerated, condoned even. “There was a time not all that long ago,” says Art Dalley, director of the Medical Anatomy Program at Vanderbilt University, “when students were taught to be insensitive, as a coping mechanism.”

Ch 2: Life After Death

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

The cadaver in the sweatpants is the newest arrival. He will be our poster man for the first stage of human decay, the “fresh” stage. The hallmark of fresh-stage decay is a process called autolysis, or self-digestion. Human cells use enzymes to cleave molecules, breaking compounds down into things they can use.

Ch 3: Life After Death

While a person is alive, the cells keep these enzymes in check, preventing them from breaking down the cells’ own walls. After death, the enzymes operate unchecked and begin eating through the cell structure, allowing the liquid inside to leak out.

“See the skin on his fingertips there?” says Arpad. Two of the dead man’s fingers are sheathed with what look like rubber fingertips of the sort worn by accountants and clerks. “The liquid from the cells gets between the layers of skin and loosens them. As that progresses, you see skin sloughage.” Mortuary types have a different name for this. They call it “skin slip.”

[…] The liquid that is leaking from the enzyme-ravaged cells is now making its way through the body. Soon enough it makes contact with the body’s bacteria colonies: the ground troops of putrefaction. These bacteria were there in the living body as well, in the intestinal tract, in the lungs, on the skin—the places that came in contact with the outside world. Life is looking rosy for our one-celled friends. They’ve already been enjoying the benefits of a decommissioned human immune system, and now, suddenly, they’re awash with this edible goo, issuing from the ruptured cells of the intestine lining. It’s raining food. As will happen in times of plenty, the population swells.

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

Stage 2: Bloat

Ch 3: Life After Death

The life of a bacterium is built around food. Bacteria don’t have mouths or fingers or Wolf Ranges, but they eat. They digest. They excrete. Like us, they break their food down into its more elemental components. The enzymes in our stomachs break meat down into proteins. The bacteria in our gut break those proteins down into amino acids; they take up where we leave off. When we die, they stop feeding on what we’ve eaten and begin feeding on us. And, just as they do when we’re alive, they produce gas in the process. Intestinal gas is a waste product of bacteria metabolism.

The difference is that when we’re alive, we expel that gas. The dead, lacking workable stomach muscles and sphincters and bedmates to annoy, do not. Cannot. So the gas builds up and the belly bloats. I ask Arpad why the gas wouldn’t just get forced out eventually. He explains that the small intestine has pretty much collapsed and sealed itself off. Or that there might be “something” blocking its egress.

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

Dead people, unembalmed ones anyway, basically dissolve; they collapse and sink in upon themselves and eventually seep out onto the ground. […] The digestive organs and the lungs disintegrate first, for they are home to the greatest numbers of bacteria; the larger your work crew, the faster the building comes down. The brain is another early-departure organ. ; “Because all the bacteria in the mouth chew through the palate,” explains Arpad. And because brains are soft and easy to eat. “The brain liquefies very quickly. It just pours out the ears and bubbles out the mouth.” Up until about three weeks, Arpad says, remnants of organs can still be identified. “After that, it becomes like a soup in there.” Because he knew I was going to ask, Arpad adds, “Chicken soup. It’s yellow.“

Ch 3: Life After Death

Muscles are eaten not only by bacteria, but by carnivorous beetles. I wasn’t aware that meat-eating beetles existed, but there you go. Sometimes the skin gets eaten, sometimes not. Sometimes, depending on the weather, it dries out and mummifies, whereupon it is too tough for just about anyone’s taste.

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

An eye cap is a simple ten-cent piece of plastic. It is slightly larger than a contact lens, less flexible, and considerably less comfortable. The plastic is repeatedly lanced through, so that small, sharp spurs stick up from its surface. The spurs work on the same principle as those steel spikes that threaten Severe Tire Damage on behalf of rental car companies: The eyelid will come down over an eye cap, but, once closed, will not easily open back up. Eye caps were invented by a mortician to help dead people keep their eyes shut.

Ch 3: Life After Death

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

“Now we’re going to set the features,” says Theo. He lifts one of the man’s eyelids and packs tufts of cotton underneath to fill out the lid the way the man’s eyeballs once did. Oddly, the culture I associate most closely with cotton, the Egyptians, did not use their famous Egyptian cotton for plumping out withered eyes. The ancient Egyptians put pearl onions in there. Onions. Speaking for myself, if I had to have a small round martini garnish inserted under my eyelids, I would go with olives. On top of the cotton go a pair of eye caps. “People would find it disturbing to find the eyes open,” explains Theo, and then he slides down the lids.

Ch 3: Life After Death

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

The last feature to be posed is the mouth, which will hang open if not held shut. Theo is narrating for Nicole, who is using a curved needle and heavy-duty string to suture the jaws together. “The goal is to reenter through the same hole and come in behind the teeth,” says Theo. “Now she’s coming out one of the nostrils, across the septum, and then she’s going to reenter the mouth. There are a variety of ways of closing the mouth,” he adds, and then he begins talking about something called a needle injector. I pose my own mouth to resemble the mouth of someone who is quietly horrified, and this works quite well to close Theo’s mouth.

Ch 3: Life After Death

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

Modern embalming makes use of the circulatory system to deliver a liquid preservative to the body’s cells to halt autolysis and put decay on hold. Just as blood in the vessels and capillaries once delivered oxygen and nutrients to the cells, now those same vessels, emptied of blood, are delivering embalming fluid.

Ch 3: Life After Death

Theo is feeling around on Mr. Blank’s neck. “We’re in search of the carotid artery,” he announces. He cuts a short lengthwise slit in the man’s neck. Because no blood flows, it is easy to watch, easy to think of the action as simply something a man does on his job, like cutting roofing material or slicing foam core, rather than what it would more normally be: murder. Now the neck has a secret pocket, and Theo slips his finger into it. After some probing, he finds and raises the artery, which is then severed with a blade. The loose end is pink and rubbery and looks very much like what you blow into to inflate a whoopee cushion.

A cannula is inserted into the artery and connected by a length of tubing to the canister of embalming fluid. Mack starts the pump. Here is where it all begins to make sense. Within minutes, the man’s face looks rejuvenated. The embalming fluid has rehydrated his tissues, filling out his sunken cheeks, his lined skin. His skin is pink now (the embalming fluid contains red coloring), no longer slack and papery. He looks healthy and surprisingly alive. This is why you don’t just stick bodies in the refrigerator before an open-casket funeral.

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

Drops of sweat bead the inside surface of Nicole’s splash shield. We’ve been here more than an hour. It’s almost over. Theo looks at Mack. “Will we be suturing the anus?” He turns to me. “Otherwise leakage can wick into the funeral clothing and it’s an awful mess.” I don’t mind Theo’s matter-of-factness. Life contains these things: leakage and wickage and discharge, pus and snot and slime and gleet. We are biology. We are reminded of this at the beginning and the end, at birth and at death. In between we do what we can to forget.

Ch 3: Life After Death

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

The point is that no matter what you choose to do with your body when you die, it won’t, ultimately, be very appealing. If you are inclined to donate yourself to science, you should not let images of dissection or dismemberment put you off. They are no more or less gruesome, in my opinion, than ordinary decay or the sewing shut of your jaws via your nostrils for a funeral viewing.

Ch 3: Life After Death

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

Sharing a room with a cadaver is only mildly different from being in a room alone. They are the same sort of company as people across from you on subways or in airport lounges, there but not there.

Ch 4: Dead Man Driving

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

The British investigators know what butchers have long known: If you want people to feel comfortable about dead bodies, cut them into pieces. A cow carcass is upsetting; a brisket is dinner. A human leg has no face, no eyes, no hands that once held babies or stroked a lover’s cheek. It’s difficult to associate it with the living person from which it came. The anonymity of body parts facilitates the necessary dissociations of cadaveric research: This is not a person. This is just tissue. It has no feelings, and no one has feelings for it. It’s okay to do things to it which, were it a sentient being, would constitute torture.

Ch 4: Dead Man Driving

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

Shanahan says 80 to 85 percent of plane crashes are potentially survivable.

Ch 5: Beyond the Black Box

The key word here is “potentially.” Meaning that if everything goes the way it went in the FAA-required cabin evacuation simulation, you’ll survive. Federal regulations require airplane manufacturers to be able to evacuate all passengers through half of a plane’s emergency exits within 90 seconds. Alas, in reality, evacuations rarely happen the way they do in simulations. […]

Could airlines do a better job of making their planes fire-safe? You bet they could. They could install more emergency exits, but they won’t, because that means taking out seats and losing revenue. They could install sprinkler systems or build crash-worthy fuel systems of the type used on military helicopters. But they won’t, because both these options would add too much weight. More weight means higher fuel costs. […]

Who decides when it’s okay to sacrifice human lives to save money?

Ostensibly, the Federal Aviation Administration. The problem is that most airline safety improvements are assessed from a cost-benefit viewpoint. To quantify the “benefit” side of the equation, a dollar amount is assigned to each saved human life. As calculated by the Urban Institute in 1991, you are worth $2.7 million. “That’s the economic value of the cost of somebody dying and the effects it has on society,” said Van Goudy, the FAA man I spoke with. While this is considerably more than the resale value of the raw materials, the figure in the benefits column is rarely large enough to surpass the airlines’ projected costs. Goudy used the example of shoulder harnesses, which I had asked him about. “The agency would say, ‘All right, if you’re going to save fifteen lives over the next twenty years by putting in shoulder straps, that’s fifteen times two million dollars; that’s thirty million.‘ The industry comes back and says, ‘It’s gonna cost us six hundred and sixty-nine million to put the things in.’

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

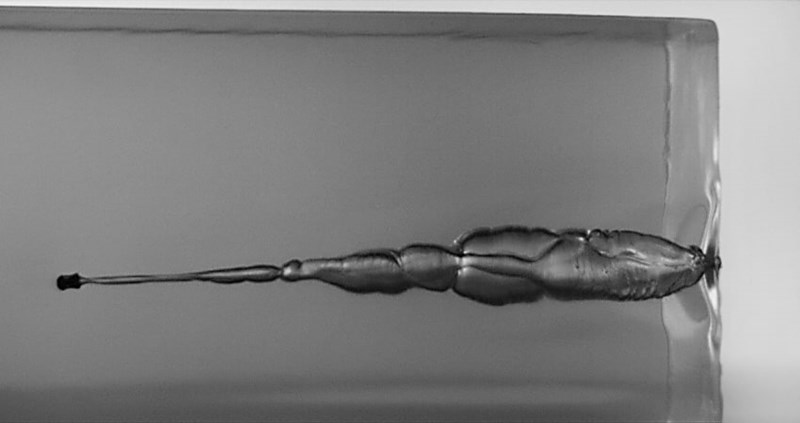

source: Norma Ammunition

I am about to fire a bullet into the closest approximation of a human thigh outside of a human thigh: a six-by-six-by-eighteen-inch block of ballistic gelatin. Ballistic gelatin is essentially a tweaked version of Knox dessert gelatin. It is denser than dessert gelatin, having been formulated to match the average density of human tissue, is less colorful, and, lacking sugar, is even less likely to please dinner guests. Its advantage over a cadaver thigh is that it affords a stop-action view of the temporary stretch cavity. Unlike real tissue, human tissue simulant doesn’t snap back: The cavity remains, allowing ballistics types to judge, and preserve a record of, a bullet’s performance. Plus, you don’t need to autopsy a block of human tissue simulant; because it’s clear, you just walk up to it after you’ve shot it and take a look at the damage. Following which, you can take it home, eat it, and enjoy stronger, healthier nails in thirty days.

Ch 6: The Cadaver Who Joined the Army

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

“The concern is that some survivor will be so taken aback that they’ll bring suit,” said Colonel Baker from his desk at a federal institution in Washington. “And there is no body of law in this area, nothing you can look to other than good judgment.” He pointed out that although cadavers don’t have rights, their family members do. “I could imagine some sort of lawsuit that is based upon emotional distress….You get some of those [cases] in a cemetery situation, where the proprietor has allowed the coffins to rot away and the corpses pop up.” I replied that as long as you have informed consent—a signed agreement from the donor stating that he has willed his body to medical research—it would seem that the survivors wouldn’t have much of a case.

Ch 6: The Cadaver Who Joined the Army

The sticking point is the word “informed.” It’s fair to say that when people donate remains, either their own or those of a family member, they usually don’t care to know the grisly details of what might be done with them. And that if you did tell them the details, they might change their minds and withdraw consent. Then again, if you’re planning to shoot guns at them, it might be good to run that up the flagpole and get the a-okay. “Part of respecting persons is telling them the information that they might have an emotional response to,” says Edmund Howe, editor of the Journal of Clinical Ethics, who reviewed Marlene DeMaio’s research proposal. “Though one could go the other way and spare them that response and therefore ethically not commit that harm. But the downside to withholding information that might be significant to them is that it would violate their dignity to an extent.” Howe suggests a third possibility, that of letting the families make the choice: Would they prefer to hear the specifics of what is being done with the donated body—specifics that may be upsetting—or would they prefer not to know?

It’s a delicate balance that, in the end, comes down to wording. Observes Baker, “You don’t really want to be telling some-body, ‘Well, what we’ll be doing is dissecting their eyeballs. We take them out and put them on a table and then we dissect them into finer and finer parts and then once we’re finished we scrape all that stuff up and put it into a biohazard bag and try to keep it together so we can return whatever’s left to you.’ That sounds horrible.” On the other hand, “medical research” is a tad vague.

“Instead, you say, ‘One of our principal concerns here at the university is ophthalmology. So we do a lot here with ophthalmological materials.'” If someone cares to think it through, it isn’t hard to come to the conclusion that someone in a lab coat will, at the very least, be cutting your eyeball out of your head. But most people don’t care to think it through. They focus on the end, rather than the means: Someone’s vision may one day be saved.

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

©1978 Vernon Miller, Fair Use

Shroud of Turin, the linen cloth in which, believers held, Jesus had been wrapped for burial when he was taken down from the cross. The shroud’s authenticity was in question then, as now, and the church had turned to medicine to see if the markings corresponded to the realities of anatomy and physiology.

Ch 7: Holy Cadaver

Dr. Barbet had become fixated on a pair of elongated “bloodstains” issuing from the “imprint” of the back of the right hand on the shroud. The two stains come from the same source but proceed along different paths, at different angles. The first, he writes, “mounts obliquely upwards and inwards (anatomically its position is like that of a soldier when challenging), reaching the ulnar edge of the forearm. Another flow, but one more slender and meandering, has gone upwards as far as the elbow.

Barbet decided that the two flows were created by Jesus’ alternately pushing himself up and then sagging down to hang by his hands; thus the trickle of blood from the nail wound would follow two different paths, depending on which position he was in. The reason Jesus was doing this, Barbet theorized, was that when people hang from their arms, it becomes difficult to exhale; Jesus was trying to keep from suffocating. Then, after a while, his legs would fatigue and he’d sag back down again.

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

Eventually, Barbet’s busy hammer made its way to what he believed was the true site of the nail’s passage: Destot’s space, a pea-sized gap between the two rows of the bones of the wrist.

Ch 7: Holy Cadaver

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

Rather than crucifying corpses, Barbet uses live volunteers, hundreds in all. For his first study, he recruited just shy of one hundred volunteers from a local religious group, the Third Order of St. Francis. How much do you have to pay a research subject to be crucified? Nothing. “They would have paid me,” says Zugibe. “Everyone wanted to go up and see what it felt like.” Granted, Zugibe was using leather straps, not nails.

Ch 7: Holy Cadaver

The first thing Zugibe noticed when he began putting people up on his cross was that none of them were having trouble breathing, even when they stayed up there for forty-five minutes. Nor did Zugibe’s subjects spontaneously try to lift themselves up. In fact, when asked to do so, in a different experiment, they were unable to. “It is totally impossible to lift yourself up from that position, with the feet flush to the cross,” Zugibe asserts. Furthermore, he points out, the double blood flows were on the back of the hand, which was pressed against the cross. If Jesus had been pushing himself up and down, the blood oozing from the wound would have been smeared, not neatly split into two flows.

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

read article on BBC

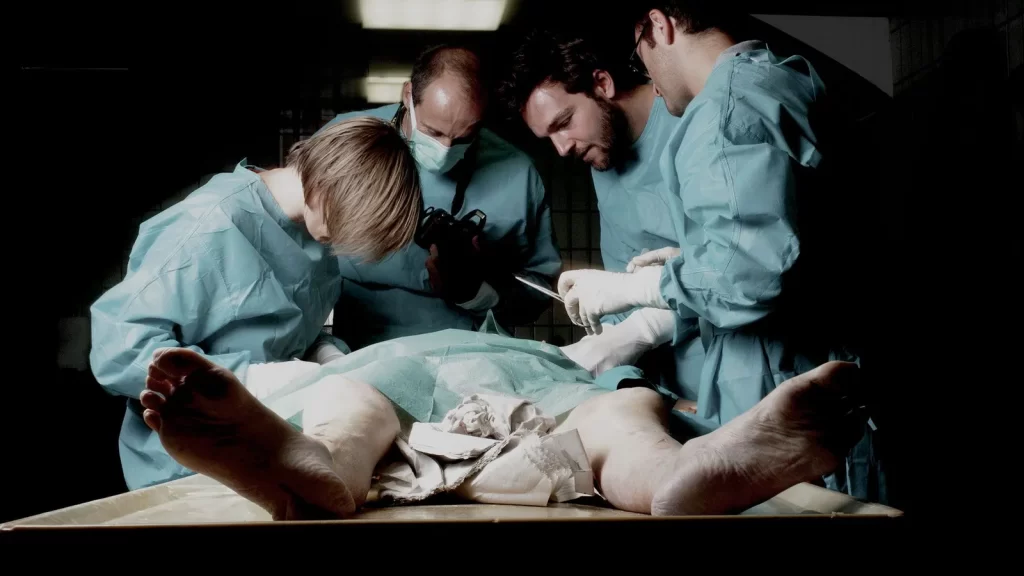

H is unique in that she is both a dead person and a patient on the way to surgery. She is what’s known as a “beating-heart cadaver,” alive and well everywhere but her brain. Up until artificial respiration was developed, there was no such entity; without a functioning brain, a body will not breathe on its own. But hook it up to a respirator and its heart will beat, and the rest of its organs will, for a matter of days, continue to thrive.

Ch 8: How to Know if You’re Dead

Since brain death is the legal definition of death in this country, H the person is certifiably dead. But H the organs and tissues is very much alive. These two seemingly contradictory facts afford her an opportunity most corpses do not have: that of extending the lives of two or three dying strangers. Over the next four hours, H will surrender her liver, kidneys, and heart. One at a time, surgeons will come and go, taking an organ and returning in haste to their stricken patients. Until recently, the process was known among transplant professionals as an “organ harvest,” which had a joyous, celebratory ring to it, perhaps a little too joyous, as it has been of late replaced by the more businesslike “organ recovery.”

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

The kidneys are placed in a blue plastic bowl with ice and perfusion fluid. A relief surgeon arrives for the final step of the recovery, cutting off pieces of veins and arteries to be included, like spare sweater buttons, along with the organs, in case the ones attached to them are too short to work with. A half hour later, the relief surgeon steps aside and the resident comes over to sew H up.

Ch 8: How to Know if You’re Dead

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

If only the soul could be seen as it left the body, or somehow measured. That way, determining when death had occurred would be a simple matter of scientific observation. This almost became a reality, at the hands of a Dr. Duncan Macdougall, of Haverhill, Massachusetts. In 1907, Macdougall began a series of experiments seeking to determine whether the soul could be weighed. Six dying patients, one after another, were installed on a special bed in Macdougall’s office that sat upon a platform beam scale sensitive to two-tenths of an ounce. By watching for changes in the weight of a human being before, and in the act of, dying, he sought to prove that the soul had substance. Macdougall’s report of the experiment was published in the April 1907 issue of American Medicine, considerably livening up the usual assortment of angina and urethritis papers. Below is Macdougall describing the first subject’s death. He was nothing if not thorough.

Ch 8: How to Know if You’re Dead

At the end of three hours and forty minutes he expired and suddenly coincident with death the beam end dropped with an audible stroke hitting against the lower limiting bar and remaining there with no rebound. The loss was ascertained to be three-fourths of an ounce. (21g)

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

With improvements in stethoscopes and gains in medical knowledge, physicians began to trust themselves to be able to tell when a heart had stopped, and medical science came to agree that this was the best way to determine whether a patient had checked out for good or was merely down the hall getting ice. Placing the heart center stage in our definition of death served to give it, by proxy, a starring role in our definition of life and the soul, or spirit or self.

Ch 8: How to Know if You’re Dead

The concept of the beating-heart cadaver, grounded in a belief that the self resides in the brain and the brain alone, delivered a philosophical curveball. The notion of the heart as fuel pump took some getting used to.

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

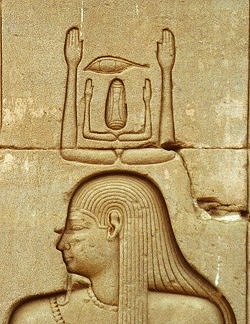

source: Global Egyptian Museum

The ancient Egyptians were the original heart guys. They believed that the ka resided in the heart. Ka was the essence of the person: spirit, intelligence, feelings and passions, humor, grudges, annoying television theme songs, all the things that make a person a person and not a nematode. The heart was the only organ left inside a mummified corpse, for a man needed his ka in the afterlife. The brain he clearly did not need: cadaver brains were scrambled and pulled out in globs, through the nostrils, by way of a hooked bronze needle. Then they were thrown away. (The liver, stomach, intestines, and lungs were taken out of the body, but kept: They were stored in earthen jars inside the tomb, on the assumption, I guess, that it is better to overpack than to leave something behind, particularly when packing for the afterlife.)

Ch 8: How to Know if You’re Dead

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

Robert Whytt was one of a handful of inquiring medical minds who attempted to use scientific experimentation to pin down the location and properties of the soul. You could see from his chapter on the topic in his 1751 Works that he wasn’t inclined to come down on either side of the heart-versus-brain debate.

Ch 8: How to Know if You’re Dead

Whytt began to suspect that the soul did not have a set resting place in the body, but was instead diffused throughout. So that when you cut off a limb or took out an organ, a portion of the soul came along with it, and would serve to keep it animated for a time. That would explain why the eel’s heart continued beating outside its body.

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

On a rational level, most people are comfortable with the concept of brain death and organ donation. But on an emotional level, they may have a harder time accepting it, particularly when they are being asked to accept it by a transplant counselor who would like them to okay the removal of a family member’s beating heart. Fifty-four percent of families asked refuse consent. “They can’t deal with the fear, however irrational, that the true end of their loved one will come when the heart is removed,” says Oz. That they, in effect, will have killed him.

Ch 8: How to Know if You’re Dead

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

Even heart transplant surgeons sometimes have trouble accepting the notion that the heart is nothing more than a pump. When I asked Oz where he thought the soul resided, he said, “I’ll confide in you that I don’t think it’s all in the brain. I have to believe that in many ways the core of our existence is in our heart.” Does that mean he thinks the brain-dead patient isn’t dead? “There’s no question that the heart without a brain is of no value. But life and death is not a binary system.” It’s a continuum. It makes sense, for many reasons, to draw the legal line at brain death, but that doesn’t mean it’s really a line. “In between life and death is a state of near-death, or pseudo-life. And most people don’t want what’s in between.”

Ch 8: How to Know if You’re Dead

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

It is astounding to me, and achingly sad, that with eighty thousand people on the waiting list for donated hearts and livers and kidneys, with sixteen a day dying there on that list, that more than half of the people in the position H’s family was in will say no, will choose to burn those organs or let them rot. We abide the surgeon’s scalpel to save our own lives, our loved ones’ lives, but not to save a stranger’s life. H has no heart, but heartless is the last thing you’d call her.

Ch 8: How to Know if You’re Dead

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

Human head transplants. If a brain—a personality—and its surrounding head can be kept functional with an outside blood supply for as long as that supply lasts, then why not go the whole hog and actually transplant it onto a living, breathing body, so that it has an ongoing blood supply?

Ch 9: Just a Head

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

source: The Bizarre History of Head Transplants

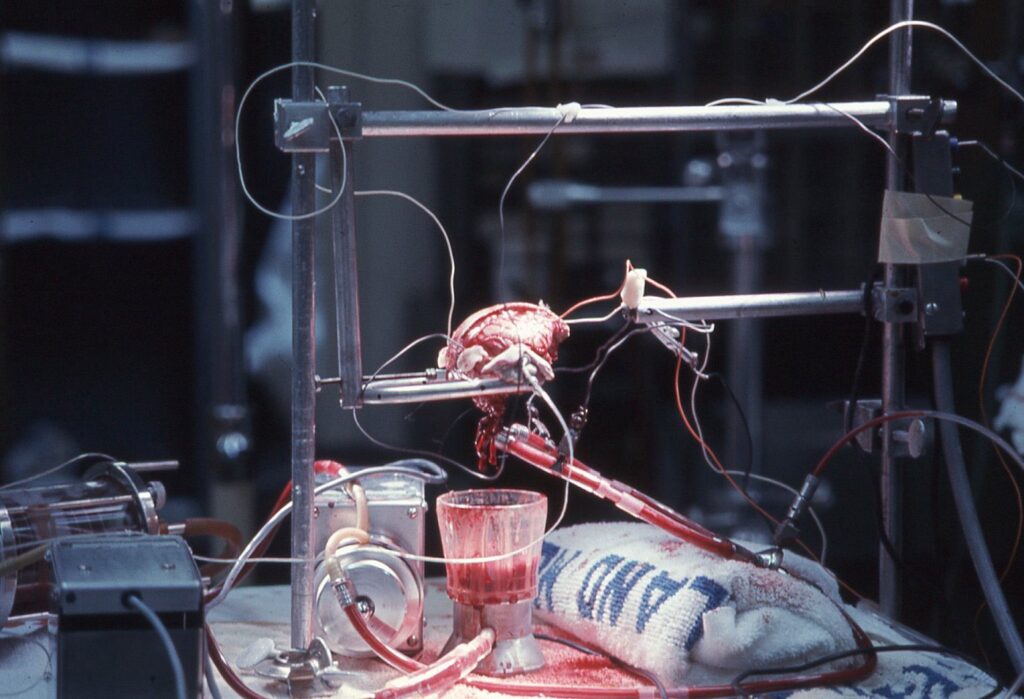

In the mid-1960s, a neurosurgeon named Robert White began experimenting with “isolated brain preparations”: a living brain taken out of one animal, hooked up to another animal’s circulatory system, and kept alive. Unlike Demikhov’s and Guthrie’s whole head transplants, these brains, lacking faces and sensory organs, would live a life confined to memory and thought. Given that many of these dogs’ and monkeys’ brains were implanted inside the necks and abdomens of other animals, this could only have been a blessing. While the inside of someone else’s abdomen is of moderate interest in a sort of curiosity-seeking, Surgery Channel sort of way, it’s not the sort of place you want to settle down in to live out the remainder of your years.

Ch 9: Just a Head

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

White figured out that by cooling the brain during the procedure to slow the processes by which cellular damage occurs— a technique used today in organ recovery and transplant operations—it was possible to retain most of the organ’s normal functions. Which means that the personality—the psyche, the spirit, the soul—of those monkeys continued to exist, for days on end, without its body or any of its senses, inside another animal.

Ch 9: Just a Head

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

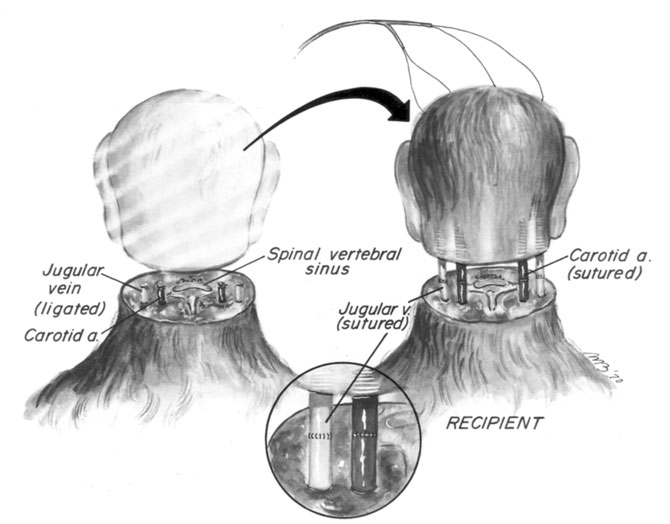

In 1971, White achieved the unthinkable. He cut the head off one monkey and connected it to the base of the neck of a second, decapitated monkey.

Ch 9: Just a Head

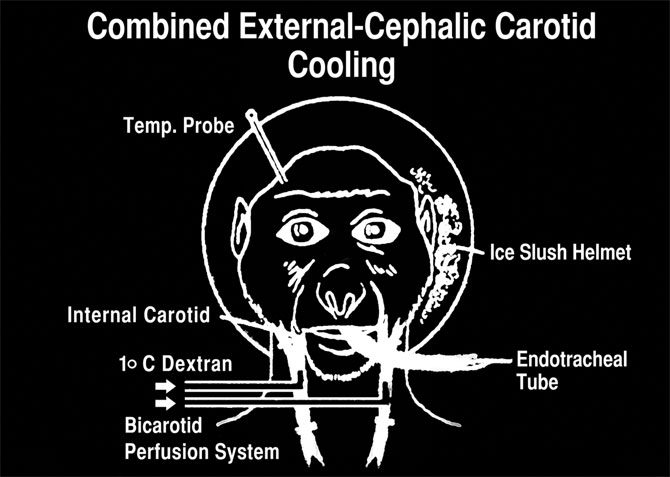

The operation lasted eight hours and required numerous assistants, each having been given detailed instructions, including where to stand and what to say. White went up to the operating room for weeks beforehand and marked off everyone’s position on the floor with chalk circles and arrows, like a football coach. The first step was to give the monkeys tracheotomies and hook them up to respirators, for their windpipes were about to severed. Next White pared the two monkey’s necks down to just the spine and the main blood vessels—the two carotid arteries carrying blood to the brain and the two jugular veins bringing it back to the heart. Then he whittled down the bone on the top of the body donor’s neck and capped it with a metal plate, and did the same thing on the bottom of the head. (After the vessels were reconnected, the two plates were screwed together.) Then, using long, flexible tubing, he brought the circulation of the donor body over to supply its new head and sutured the vessels. Finally, the head was cut off from the blood supply of its old body.

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

source here

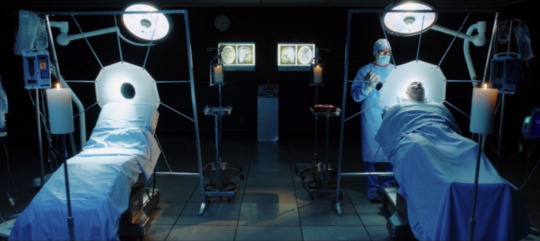

White thinks of the operation not as a head transplant, but as a whole-body transplant. Think of it this way: Instead of getting one or two donated organs, a dying recipient gets the entire body of a brain-dead beating-heart cadaver. Unlike Guthrie and Demikhov with their multiheaded monsters, White would remove the body donor’s head and put the new one in its place. The logical recipient of this new body, as White envisions it, would be a quadriplegic. For one thing, White said, the life span of quadriplegics is typically reduced, their organs giving out more quickly than is normal. By putting them—their heads— onto new bodies, you would buy them a decade or two of life, without, in their case, much altering their quality of life. High-level quadriplegics are paralyzed from the neck down and require artificial respiration, but everything from the neck up works fine. Ditto the transplanted head.

Ch 9: Just a Head

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

“You’re dealing with an operation that is totally revolutionary. People can’t make up their minds whether it’s a total body transplant or a head transplant, a brain or even a soul transplant. There’s another issue too.

Ch 9: Just a Head

There are other countries, countries with less meddlesome regulating bodies, that would love to have White come over and make history swapping heads. “I could do it in Kiev tomorrow. And they’re even more interested in Germany and England. And the Dominican Republic. They want me to do it. Italy would like me to do it. But where’s the money?” “Who’s going to fund the research when the operation is so expensive and would only benefit a small number of patients?”

Let’s say someone did fund the research, and that White’s procedures were streamlined and proved viable. Could there come a day when people whose bodies are succumbing to fatal diseases will simply get a new body and add decades to their lives—albeit, to quote White, as a head on a pillow? There could. Not only that, but with progress in repairing damaged spinal cords, surgeons may one day be able to reattach spinal nerves, meaning these heads could get up off their pillows and begin to move and control their new bodies. There’s no reason to think it couldn’t one day happen.

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

Would any culture go so far as to use human flesh as food simply out of practicality?

Ch 10: Eat Me

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

Anthropologists will tell you that the reason people never dined regularly on other people is economics. While there existed, I am told, cultures in Central America that actually ranched humans—kept enemy soldiers captive for a while to fatten them up—it was not practical to do so, because you had to give up more food to feed them than you’d gain in the end by eating them. Carnivores and omnivores, in other words, make lousy livestock. “Humans are very inefficient in converting calories into body composition,” said Stanley Garn, a retired anthropologist with the Center for Human Growth and Development at the University of Michigan. I had called him because he wrote an American Anthropologist paper on the topic of human flesh and its nutritional value. “Your cows,” he said, “are much more efficient.”

Ch 10: Eat Me

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

credit: Seattle Times

Is there a more economical way to dispose of the body? A more environmentally friendly way? Could something useful be done with the remains? With our own deaths, the disposal of the body was for centuries incorporated into the ritual of memorial and farewell. Mourners are present at the lowering of the coffin and, until more recently, the measured, remote-control conveyance of the casket into the cremation furnace. With the majority of cremations now done out of view of the mourners, the memorial has begun to be separated from the process of disposal. Does this free us to explore new possibilities?

Ch 11: Out of the Fire, Into the Compost Bin

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

If you wanted to fertilize your garden with dead people, you were better off doing it the Hay way. Dr. George Hay was a Pittsburgh chemist who advocated pulverizing dead bodies so that they would—to quote an 1888 newspaper article on the topic—”return to the elements as soon as possible, if for no other purpose than to furnish a fertilizer.” Here is Hay, quoted at length in the article, which is pasted into a scrapbook belonging to the Historical Collection of the Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts:

Ch 11: Out of the Fire, Into the Compost Bin

The machines might be so contrived as to break the bones first in pieces the size of a hen egg, next into fragments of the size of a marble, and the mangled and lacerated mass could next be reduced by means of chopping machines and steam power to mincemeat. At this stage we have a homogeneous mixture of the entire body structures in the form of a pulpous mass of raw meat and raw bones. This mass should now be dried thoroughly by means of steam heat at a temperature of 250F. because firstly we wish to reduce the material to a condition convenient for handling and secondly we wish to disinfect it. Once in this condition, it would command a good price for the purpose of manure. Which brings us, ready or not, to the modern human compost movement.

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

Tim Evans was the first person to compost a human body. In 1998, Evans procured the body of a ne’er-do-well whose family had donated him to the university. “He never knew he was going to end up as compost guy,” recalled Evans, when I telephoned him. This was probably just as well. To supply the requisite bacteria to break down the tissue, Evans composted the body with manure and soiled wood shavings from stables. The dignity issue rears its delicate head.

Ch 11: Out of the Fire, Into the Compost Bin

And because the man was buried whole, Evans had to go out with a shovel and rake to aerate him three or four times. This is why Wiigh-Masak plans to break bodies up, with either vibration or ultrasound. The tiny pieces are easily saturated with oxygen and so quickly composted and assimilated that they can be used immediately for a planting. It was also, in part, a matter of dignity and aesthetics. “The body has to be unrecognizable while it composts,” says Wiigh-Masak. “It has to be in small pieces. Can you imagine the family sitting around the dinner table and someone says, ‘Okay, Sven, it’s your turn to go out and turn Mother’?”

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

There is but one way to be an organ on a shelf, and that is to be plastinated. Plastination is the process of taking organic tissue—a rosebud, say, or a human head—and replacing the water in it with a liquid silicone polymer, turning the organism into a permanently preserved version of itself.

Ch 11: Out of the Fire, Into the Compost Bin

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

Here’s the other thing I think about. It makes little sense to try to control what happens to your remains when you are no longer around to reap the joys or benefits of that control. People who make elaborate requests concerning disposition of their bodies are probably people who have trouble with the concept of not existing. Leaving a note requesting that your family and friends travel to the Ganges or ship your body to a plastination lab in Michigan is a way of exerting influence after you’re gone—of still being there, in a sense. I imagine it is a symptom of the fear, the dread, of being gone, of the refusal to accept that you no longer control, or even participate in, anything that happens on earth. I spoke about this with funeral director Kevin McCabe, who believes that decisions concerning the disposition of a body should be made by the survivors, not the dead. “It’s none of their business what happens to them when they die,” he said to me. While I wouldn’t go that far, I do understand what he was getting at: that the survivors shouldn’t have to do something they’re uncomfortable with or ethically opposed to.

Ch 12: Remains of the Author

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

◃ Back