A riveting story of the rise and fall of Uber and Travis Kalanick. Highly recommended.

What I learnt from Super Pumped:

- Importance of company culture

- Do what it takes but know what not to do

- Being first doesn’t matter, being the best does

- The law isn’t what is written, it’s what is enforced

- Uber’s ingenious solutions to tackle problems

Summary / Excerpt:

Scour

Kalanick dropped out of ULCA to join his friends to build Scour, a search engine for p2p file sharing. A VC offered them a term sheet with a “no-shop clause”. They later found themselves mired in negotiations with the VC to the point that they either make the deal or walk away. The episode would change the way Kalanick saw VCs for the rest of his life.

Red Swoosh

In 2001, Kalanick founded Red Swoosh, yet another p2p file sharing company. At one point, Red Swoosh was running out of money, an employee dipped into the company’s payroll tax withholdings to fund operations. The employee left the company, and Kalanick was stuck with the blame. This incident would form the basis for his difficulty trusting people. After 6 years of tireless hustling, Red Swoosh was sold to Akamai for ~$20m, and Kalanick netted ~$2m post-tax.

The idea of Uber

Garret Camp, the co-founder of StumbleUpon, had moved to San Francisco with hopes of growing his startup. SF was small enough that one could survive without owning a car, but still large enough for a person to be annoyed they didn’t have one.

The taxi dispatching system was ancient and unreliable. It compelled Camp to create hacks and workarounds. One trick he devised was dialling up all the major taxi services in the city to ask for a pickup. He’d take the first that arrived and ignore the rest. Soon he got caught and blacklisted.

Later, Camp and Kalanick co-founded UberCab. They’d market UberCab to professionals in dense cities and try to make it feel exclusive, almost like a club.

credit: techapp.com

Early Days of UberCab

Upon agreeing to the CEO role, Kalanick insisted on being given a larger ownership stake in the company. He didn’t care about his salary, he wanted power.

The first version of UberCab was not an app. Users logged in to a desktop computer browser, navigated to UberCab.com, requested a black car and would receive a ride within ten minutes or less. It was more expensive, but the idea was people would pay more for the reliability and convenience of on-demand service. Soon enough, the company farmed out development, and contract programmers hacked together a rudimentary version of an UberCab iPhone app. It was buggy and slow, but it worked.

In the early days, they cold-called hundreds of limo drivers around SF and pitched them to drive for UberCab. Later, the company struck a deal with AT&T, wherein they bought thousands of iPhones in bulk at a discounted price. Then they’d give out iPhones pre-loaded with Uber app to the drivers. The AT&T deal brought a critical mass of drivers onto the network.

To kickstart demand, UberCab would dole out incentives to both drivers and riders. Riders would get a free first trip upon signing up for the app; drivers were promised hundreds of dollars in bonuses if they completed a minimum number of trips.

In late 2020, UberCab had been served with a cease and desist order; the company was breaking the law by skirting existing transportation regulations. Every day UberCab was in operation, the company faced fines of up to $5,000 per trip. Kalanick didn’t miss a beat and said “We ignore it. We’ll drop ‘Cab’ from our name.” UberCab was now known as “Uber,” and it was staying open for business.

UberX

Zimride a long-distance carpooling startup pivoted to become Lyft. They offered p2p ride sharing. Uber then decided to go head-to-head with Lyft with their new low-cost option UberX.

Wherever Lyft went, Uber showed up to harass them. One of Lyft’s most effective grassroots tactics was holding what they called “driver events,” small parties for a hundred people that Lyft was trying to court as drivers. Kalanick made sure to ruin those for Lyft, too. He’d send his own employees to the events, where they would show up in jet black T-shirts— Uber’s signature colour—carrying plates filled with cookies, each with the word “Uber” written in icing. Each Uber employee had a referral code printed on the back of their T-shirt. The codes were for Lyft drivers to enter when they signed up for Uber, earning them a bonus.

Uber wasn’t just fighting for a piece of the taxi and limousine market. It was competing against every mode of transportation in existence. Uber could reach a point where it’s cheap and convenient enough that it becomes a preferable alternative to owning a car.

Buy the Chicken

Uber had discovered a winning formula to expansion. But each new city required capital, upfront investment to kickstart what they called the demand “flywheel.” Drivers wouldn’t work for Uber unless there was enough demand from riders. And new riders wouldn’t sign up or return unless there was a critical mass of available drivers. It was a classic chicken-and-egg problem.

Uber solved that problem by straight-up buying the chicken. Uber began torching hundreds of thousands of dollars, giving away the money as driver subsidies. They paid bonus cash when a driver completed a certain number of rides or drove for a certain number of days. Uber would also flood the rider side of the market with cash, doling out thousands of dollars in free rides to new customers.

All about Growth

A job at Uber wasn’t just a job, after all — it was a mission, a calling. If you weren’t ready to stay late at the office and work nights and weekends, you shouldn’t be working at Uber. Company-wide dinner service — a perk that most large Silicon Valley companies offered for those who worked after hours — wasn’t served until 8:15 pm. That meant you couldn’t work an extra hour after 5pm and strategically grab a free meal at 6pm on your way out the door. You’d have to work an extra 3.25 hours to get your meal.

In New York in 2015, when Mayor Bill de Blasio threatened to cap the number of cars on the road, Uber tweaked the software inside of its app for New York-based riders to show what it called “De Blasio’s Uber.” That option showed fewer animated cars driving around on the mini-map inside the Uber app, with approximate wait times of up to a half hour. Users were invited to “take action,” and were presented with a button inside the app that emailed the mayor and the city council directly with a form letter prewritten by Uber. By the end of the campaign, the mayor’s office had received thousands of letters from upset users protesting the potential ban. De Blasio ended up shelving the proposal.

The strategy was extremely effective. So effective that Uber decided to systematise and weaponise it across the company. They built automated tools to spam lawmakers and rally users. With easy, in-app buttons, users could send emails, texts, and phone calls to elected officials whenever an important legislative matter was up for debate.

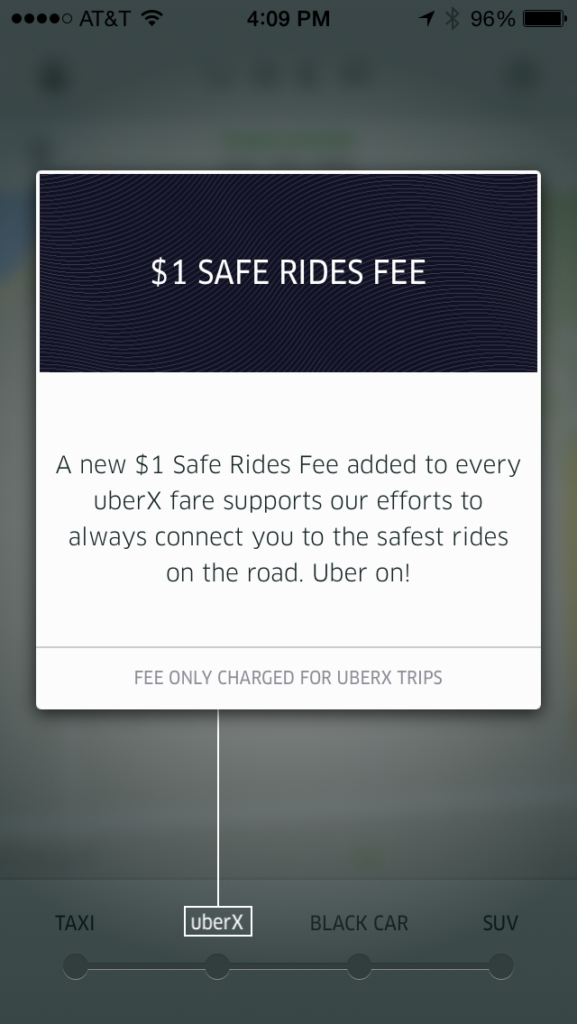

In 2014, Uber introduced “Safe Rides Fee,” a new charge that added $1 to the cost of each trip. Uber billed it as necessary for passengers: This Safe Rides Fee supports our continued efforts to ensure the safest possible platform for Uber riders and drivers, including an industry-leading background check process, regular motor vehicle checks, driver safety education, development of safety features in the app, and insurance.

The reality was much less noble. As Uber’s insurance costs grew exponentially, the “Safe Rides Fee” was devised to add $1 of pure margin to each trip.

Deceiving Apple

To identify fraudsters, Uber used InAuth service to track down the device identification number of the iPhone used to install the app, a technique known as “fingerprinting”. InAuth required far more data than the average smartphone app in order to triangulate the users’ IMEI numbers. Their service blatantly violated Apple’s rules regarding user privacy.

One of the engineers had an idea to trick Apply by using “geofencing”. If the Uber app was used within the Bay Area or near Apple’s Cupertino headquarters, it wouldn’t run the InAuth “library” of code, which asked for the personal data needed to fingerprint phones. It turned out, not all of Apple’s App Store code reviewers were located in Cupertino and the Bay Area. Eventually, an Apple reviewer who wasn’t based in California stumbled upon the InAuth code library. Uber was actively deceiving Apple in an elaborate and sophisticated way.

Deceiving Authorities

Greyball is a software tool Uber used to systematically deceive and evade authorities.

In the fall of 2014, as the company tried to launch UberX in Philadelphia, the Philadelphia Parking Authority sent a stern message to drivers. “If we find a civilian car operating as an UberX, we will take the vehicle off the streets. We will impound the vehicle,” a PPA official said at the time. The PPA started creating fake Uber accounts to conduct sting operations; when Uber drivers showed up, PPA officials impounded their cars and issued thousands of dollars in fines. It was effective; people became too scared to drive for Uber.

So Uber engineers, fraud team members and field operatives came up with about a dozen ways to spot authorities. After Uber managers felt confident they had spotted police or parking enforcement, all it took was the addition of a short piece of code—the word “Greyball” and a string of numbers—to blind that account to Uber’s activities. It worked extremely well; the PPA never noticed the deception and car impound rates plummeted.

On Hiring & Evaluation

Kalanick saw HR as a tool to onboard swaths of new talent and quickly dismiss the inevitable bad hires, rather than as a way to retain and manage Uber’s standing workforce.

Performance reviews were little more than the “T3 B3 process“, followed by a largely arbitrary number score. Those scores fluctuated wildly, often depending on how close a given employee was with the manager or department head who was doing the grading. And the backdrop to the entire grading system was Uber’s 14 cultural values. Managers made their evaluations in private and came back with a score, with little explanation of how they arrived at it. And one’s year-end bonuses, salary increases, and overall career trajectory inside Uber hinged upon that score.

Over time, scoring and advancing through the organization required politicking, cosying up to the right leaders, and, above all else, delivering products or ideas that led to growth. Your quality as an employee, or as a person, didn’t really matter. At the end of the day, growth—trips, users, drivers, revenue—won all arguments.

Uber’s employee performance system had created an alpha, kill-or-be-killed environment.