Part 1: Network Effects

- A network effect describes what happens when products get more valuable as more people use them

- Network effect is a duality of product and network

- “Network” is defined by people who use the product to interact with each other. The entire ecosystem stays on becuase the value is in bringing everyone together

- “Effect” describes how value increases as more people start using the product

- Most products these days are low technical risk – meaning they won’t fail because the teams can’t execute on the engineering side to build the products – but they are generally also low defensibility. When something works, others can follow – and fast.

- Network effects are one of the only protective barriers in an industry where competition is fierce, and defensive barriers are weak

- Metcalfe’s law (value = n^2) is irrelevant in building a networked product as it leaves out important phases of building a network

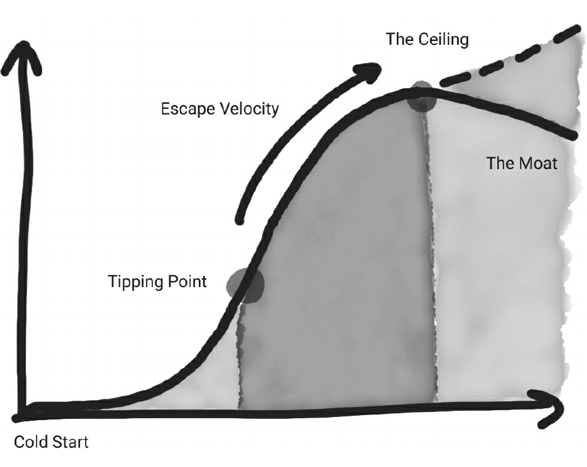

- The Cold Start Framework is made up of 5 stages for creating, scaling, and defending the network effect

➊ The Cold Start Problem

➋ Tipping Point

➌ Escape Velocity

➍ Hitting the Ceiling

➎ The Moat - Network effect is not one singular effect, but rather 3 distinct underlying forces

➊ Acquisition Effect

➋ Engagement Effect

➌ Economic Effect - The Cold Start Theory aims to provide a road map for any new product team to leverage in their work

Part 2: The Cold Start Problem

- The Cold Start Problem happens when users don’t find what they want, then they’ll churn. It leads to a self-reinforceing destructuve loop. Chen calls it “anti-network effect”

- The solution to the Cold Start Problem starts by understanding how to add a small group of the right people, at the same time, using the product in the right way. The “atomic network” is the key to get this initial network off the ground

- The “atomic network” is the smallest possible network. It needs to have enough density and stability to break through early anti-network effects and ultimately grow on its own. Ask

➊ Who’re the first, most important users to get onto a nascent network?

➋ Why are they the target?

➌ How do you seed initial network so that it grows in the way you want? - Atomic networks often have “sides”, whether they are buyers and sellers, or content creators and consumers. Generally one side of the network will be eaiser to attract. However, the most important part of any early network is attracting and retaining the hard side of a network

- “Solve a Hard Problem” by designing a product that is sufficiently compelling the hard side of a network

- The first stage of creating a network is the hardest and some will call it a “chicken and egg” situation or needing to “bootstrap” a community. Chen calls it the “Cold Start Problem”

- Solving the Cold Start Problem requires a team to launch a network and quickly create enough density and breadth such that the user experiecne can improve in leaps and bounds. Density and interconnectedness is key

- It’s important for new products to have a hypothesis for the size of the network even before you begin. The size of an initial network helps determine a launch strategy

- Do an analysis on the size of the network (on the X-axis) plotted against a set of important engagement metrics (Y-axis) to find out the number of users needed before the product experience becomes good eg Facebook’s growth maxim “10 friends in 7 days”

- The network product should be launched in its simplest possible form – not fully featured – so that it has a dead simple value proposition. The target should be on building a tiny, atomic network and focus on building density, ignoring the objection of “market size”. And finally, the attitude in executing the alaunch should be “do whatever it takes” – even if it’s unscalable or unprofitable – to get momentum without worrying about how to scale

- The Hard Side for marketplaces is usually the supply side. To solve the Cold Start Problem for marketplaces, often the first move – as it was for Uber – is to bring a critical mass of supply onto the marketplace. But once the supply has arrived onto the network, it’s time to bring in demand – the buyers and users that will form the bulk of the network. Once that’s working tho, it becomes all about supply again.

Supply → Demand → Supply → Supply → Supply - Choice matters a lot for two-sided marketplaces. As a result, the critical threshold to get to a good product experience are much larger. The higher the requirement, the harder it is to get started, but the more defensibe the product is in the long run.

- Start with underserved segments on the hard side – whose users may not be very attractive customers on their own (the long tail) and to apply Christensen’s disruption theory

- The ideal product to drive network effects combines both factors:

➊ The product idea itself should be as simple and easily understadnable as possible

➋ It should simultatneously bring together a rich, complex, infinite network of users that is impossibe to copy by competitors - Freemium model: give enough time for the users to get the full expeirence of the product eg. Zoom caps at 40mins

- Charging customers directly is a straightforward way to generate revenue, but it adds friction for every new users to join the network. It’s hard enough to build an atomic network; why make it even harder by erecting barriers? Withouth being able to build out a network quickly, growth channels like variality are more muted.

- Inversion: work backwards to solve problems. Start with the moments where the network has broken down. Uber calls these moments Zeros. When the point of the product is to interact with other particiaptns in the network, a zero means that its value can’t be fulfilled, which means users will bounce and possible never come back again

- To consistently ensure that people never experience zeroes, the netowrk needs to be built out substantially, and it needs to be active too

- Second order of getting a zero. The real cost of a zero is not just at the moment where it’s experienced, but rather, the lingering destructive effects afterward. Users who get “zeored” often churn and come to believe. the service isn’t reliable. It’s not possible to sustain a strong network when a large percnetage of users are churning

- The Cold Start Problem doens’t need to just be solved once; its needs to be dealt with over and over

Part 2: The Tipping Point

- Tipping Point happens when many atomic networks expand into the market at scale → start to gain traction / momentum

- Strategies should be oriented around tipping over entire markets, rather than launching individual atomic networks once at a time

- Strategies to tip over a market

➊ Invite-only

➋ Come for the tool, stay for the network

➌ Paying up

➍ Flintstoning

➎ Always be Hustling - Invite-only is often used to suck in a large network through viral growth. The invite mechanics work like a copy-and-paste feature. They also provide a better “welcome experience” for new users

- Invite-only cons:

– It’s often seen as risky cos it can kill the topline growth rate of your product

– it requires extra functionalities - The idea of “Come for the tool, stay for the network” is to initially attract users with a single player tool and then, over time, get them to participate in a network. The tool helps get to initial critical mass. The network creates long term value for users and densibility for the company. The tight coupling of tool and network matters

- Tool-to-network shift can be hard

- For networked products, in the earliest stages, somtemes it makes sense to spend – often wildly to pay up for growth. The goal is to get the market to hit the Tipping Point, driving towards strong positive network effects, and then pull back the subsidies.

- The common wisdom was, “If you have a chicken and egg problem – buy the chicken“

- Financial levers can be a powerful force to rapidly accelerate a market towards the Tipping Point esp for those that are close to the money. However, they should only be executed at the right time

- Uber had various financial strucrues in place to achieve different goals in managing the hard side and shift the balance of supply and demand eg surge pricing, DxGy

- Sometimes the concept of “paying up” is less about financial spending and much more about taking time and effort – as smaller companies have to do when they partner with larger platers. These partnerships are often asymmetrical,where the smaller player must customeis and build product for their partner, in exchange for access to disturbition aor revenue

- One critique of subsidising networks is like “selling a dollar for nenety cents”. But a new networked products is better off taking on the risk of subsidising the network up front, and the improving the economics over time

- Once you are able to create a few atomic networks, you might want to buy your way into an entire market, so to accelerate a network past the Tipping Point

- “Flintstoning” is a metaphor for footmobile, where missing product fundctionality is replaced with manual human effort. The goal is just to manually fill in critical parts of the network, until it can stand on its own. Build an extremely stripped down version of the solution (a MVP) with heaps of manual stuff on the backend that doesn’t scale

- Flinstoning can be thought of as a spectrum

➊ Fully manual, human-powered efforts

➋ Hybrid

➌ Automated, powered by algorithms - Paul Graham advocates that B2B startups think about doing consulting to start, treating an initial set of customers as if they were consulting clients. By building the functionality they need on an ad hoc basis, and then generalising, they have a better chance to hit product-market fit – even though this approach won’t scale

Part 3: Escape Velocity

- Dropbox divided its users into High Value Actives (HVAs) and Low Value Actives (LVAs) which was useful as a quality indicator. It could be overlaid into the strategies for marketing channels and partnership to make sure HVAs were being acquired

- Escape Velocity stage is all about working furiously to strengthen network effects and to sustain growth

- The netowrk effect is a braoader umbrella term that can be broken down into:

➊ Acquisition Effect

➋ Engagement Effect

➌ Economic Effect - Acquisition Effect is powered by viral growth, and a positive early user experience that compels one set of users to invite others into the network resulting a low-cost, highly efficeitn user acuiqistion.

- Engagement Effect describes how a denser network creates higher stickiness and usage from its users. Engagement effect increases interaction between users as networks fill in by conceptually moving users up the “engagement ladder”. This is done by introducing people to new use cases via incentives, marketing/communications, and new product features.

- Economic Effect is how a business model – inclulding profitability and unit economics – improves over time as a network grows eg monetisation levels, conversions in key monetisation flows and revenue per users

- Growth Accotungin Equation

Gain/loss in active users = New + Reactived – Churned

Acquisition Effect

- K Factor can be used to measure acquisition network effect

- Acquisition Effect can exist independently of the Engagement or Economic effect. You can acquire a lot of customers but still have a network that ultimately isn’t sticky eg chain letters

Engagement Effect

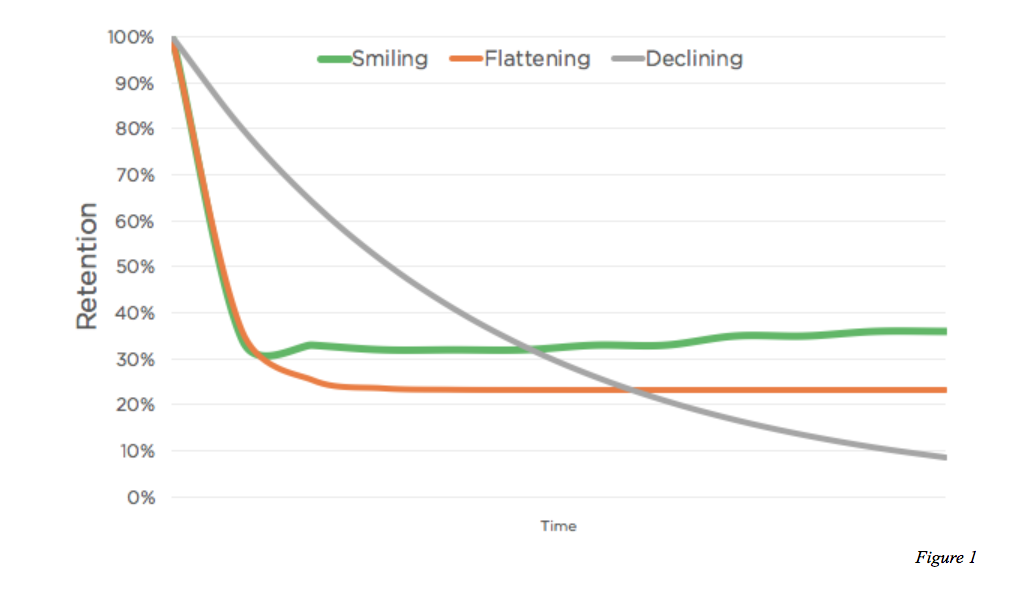

- Cohort retention curves are the foundational method for understadning whether a product is working or not

- As a rough benchmark for evaluating startups at Andreessen Horowitz, Chen often look for a minimum baseline of 60% retention after day 1, 30% after day 7, and 15% at day 30, where the curve eventually levels out

- New use cases drive more engagement

- Segment user to search for a “lever” that will move users form one level of engagement to the other

- Examinining a power user segment and trying to understand what makes them unique. However, correlation does not mean causation → Use A/B testing

- Engagement loop describes how users derive value from others in a network in a step-by-step process. Improving any step in the loop benefits all downstream actions

- The Escape Velocity phase ia about accelearting these loops, by making each stage of the loop perform better eg for a marketinplace listing, how might you make creating a listing eaiser? Can the purchase process be one click, so that the conversion rates are higher

- Networked products have the unique capability to reactive churned users which in turn grows the active user count

- These churned users are sometimes called “dark nodes.” When they are surrounded by deeply engaged colleagues and friends, even if they’ve been inactive for months, they are often flipped back into an active user

- Key question to ask related to reactivation: what is the experience of a churned user? If you’re inactive, what kinds of notifications are you getting from other users, and are they compelling enough to bring you back? If a user wants to reactive, how hard is it?

Economic Effect

- Economic Network Effect is how a business model – inclulding profitability and unit economics – improves over time as a network grows.

- Economic effect is sometimes driven by data network effect – the ability to better understand the value and cost of a customer as a network gets larger. This elps in driving higher efficiency when promotions, incentives, and subsidies into a network.

- The Economic network effect, alongside its siblings in acquisition and engagement, provide a strong defense against potential upstarts

- Products with a strong Economic Effect are able to maintain premium pricing as their networks grow, because switching costs become higher for participants who might be looking to join other networks.

Part 4: The Ceiling

- “The Ceiling” happens as products bump against an ongoing range of problems — when growth stalls, network effects weaken, and hard decisions must be made.

- The Ceilling happens for a variety of reasons, including…

➊ Saturation

➋ The Law of Shitty Clickthroughs (Degradation of marketing channels)

➌ When the network revolts

➍ Overcrowding

- Jeff Jordan’s strategy was to grow eBay by adding layers and layers of new revenue – like “adding layers to the cake”

- What looks like an exponential growth curve is often a series of lines layered quickly on top of each other

- Both network saturation and market saturation can slow down growth

- Market saturation caps the total number of people on the network

- Network saturation caps the effectiveness of your engagement over time as the interconnections slowly diminish in incremental value

- Solutions to combat saturation

➊ Adjacent user

➋ New formats

➌ New Geographies - The adjacent user theory: the adjacent users are awares of a product and possibly tried using it, but are not able to successfully become an engaged user. This is typically because the current product positioning or experience has too many barries to adoption for them

- The systematic evaluation of the network of networks that consituated instragram was to constantly figure out the adjacent set of users whose experience was subpar, rather than focusing on the core network of Power Users

- In the framework of the Adjacent User, teams need to continually evolve their offering to attract the next set of sellers or creators to their platform

- In the framework of adding layers to a cake, serving each adjacent network is like adding a new layer. Doing this requires a team to think about new markets, rather than listening to their vocal core markets – a hard feat when the core market generates most of the revenue. For the core market, there’s a different way to grow: adding new formats for people to connect and engage with each other

- New formats still fundamentally tap into the same network, but provide a new interaction that might better support new use cases eg SnapChat’s stories

- The Law of Shitty Clickthroughs says every marketing channel degrades over time

- The degradation of marketing channels is an existential threat to a products’ network effects

- The usual response is simply to pour more money into marketing – but this often creates problems

- The solution to the Law of Shitty Clickthroughs is to embrace its inevitability. The best practice is to constantly layer on new channels

- Whereas a traditional product might lean more deeply into spending on sales and marketing, networked products can be more efficient by growing without spend, by optimising their viral loops

- The Law of Shitty Clickthroughs is best countered through improving network effects, not by spending more on marketing

Part 5: The Moat

- The moat is about a successful network that defends its turf, using network effects in a perpetual battle against smaller networks trying to enter the market

- Effective competitive strategy is about who scales and leverages their network effects in the best way possible, who’s doing the best job amplifying and scaling their acquisition, engagement and economic effects

◃ Back