Reviews: A fascinated story entails the rise and fall of WeWork. How the collision of 3 forces: the charismatic Adam Neumann, unbridled optimism, and cunning salesmanship drove WeWork into the ground.

Heaps of wtf moments that left me aghast like buying the latest Gulfstream for $63m while they lost $9m the prior year. Yet the board approved the purchase, unanimously.

A page-turner, strongly recommended.

Summary:

Chapter 1: The Hustler

- Neumann was a gifted salesman selling baby clothes

- Neumann has dyslexia

- Neumann wanted to be a millionaire

Chapter 2: Greenhorns

- Neumann’s idea of converting Jay Guttman (the landlord)’s building into a coworking space – Green Desk

- Green Desk

50% : Neuman + McKelvey + Gill Haklay

50% : Guttman - In a year and a half, Guttman bought the trio out, each got 500K

Chapter 4: Physical Facebook

- Green Desk’s success in Dumbo didn’t just show that there was a demand for communal office space. Neumann and McKelvey also saw it as an indication of a broader generational shift.

- WeWork is about the tight-knit communities – a physical facebook

- Neumann and McKelvey personally bet on WeChat

Chapter 5: Manufacturing Community

- Lisa Skye was the very first community manager

- Skye heavily relied on Craiglist to recruit tenants (members)

- Skye also seeks members from people working at nearby Starbucks

- Part of the WeWork appeal was the aesthetic

- Neumann believed that engagement among members would be key to WeWork’s growth

- WeWork’s offices—which would later add 1990s arcade games and craft beer on tap—appealed firmly to those craving this urban landscape tinged with hipster chic, hitting on what would turn out to be a geyser of demand.

- McKelvey focused on the operation. Neumann was the dealmaker in chief, hunting for new offices and new investors

- Rather than buying professional-quality furnishings, Danny Orenstein (head of development) and colleagues found themselves shuttling to Ikea in Zipcars, stuffing them full with tabletops and light fixtures.

- Neumann prized speed. The pace of expansion would impress future investors and bring in new revenue to cover costs. He took to set opening dates for floors that staff thought were arbitrary and unrealistic. Then he cranked up the pressure by advertising an opening date to new members that staff figured was impossible to hit. But they had to, and they did.

- tech happy hours and events held at WeWork offices proved a successful way to lure new members.

PART II

Chapter 6: The Cult of the Founder

- If silicon valley were a rocket, venture capital would be its fuel

- WeWork’s profit margins at its buildings, before other expenses, looked like some software companies.

- Neumann insisted WeWork wasn’t a real estate company, WeWork was more like a services startup, people paying for outsourced offices and work culture

Chapter 7: Activate the Space

- Neumann took out a scrap of paper and started to scribble numbers. Here is what your stock will be worth when WeWork is worth $500 million, he would say. And here it is at $1 billion. And here it is at $5 billion. Employees stared wide-eyed, seeing their stock grant swell from, say, $10,000 to $100,000 and then half a million dollars.

- The tour was key. Guided by some of his deputies who had worked in the startup scene, Neumann obsessed over details, telling staff to “activate the space”—to show that WeWork was bursting with life and energy, that it was dramatically different from the sterile, boring offices of the past.

- The cherry on top was the serendipitous event. When an employee running the front desk got the order to “activate the space,” it meant a mad dash to throw an impromptu party with pizza, ice cream, or margaritas. The manager then sent an email to members and WeWork employees to gather in the common area for the free goods—without mentioning that investors were in tow. As the jeans-clad workers mingled over ice cream sundaes or drinks, Neumann whisked his guests by the commotion, sometimes remarking something like “events like this are always happening here.” He’d then continue walking them through the glassy hallways, past the beer on tap and the arcade game.

- as he told them, each location was spitting out profit margins of more than 30%

Chapter 8: Me Over We

- Neumann raised 40m, but a large chunk went into his bank a/c

- The company lent 9m to We Holdings LLC, the entity Neumann created with McKelvey that held their shares in WeWork

- As WeWork’s success with investors grew, Neumann’s head grew with it – from flying a private jet to buying a $10m house

- Neumann personally invested in the building that WeWork rent

- Neumann is on both sides: tenant, using the money of Benchmark and other investors to sign the deal, and landlord, using his own funds

- the board told Neumann that WeWork shouldn’t be using its money to buy real estate

Chapter 9: Mutual Fund FOMO

- WeWork was offering “space as a service”—a play on the “software as a service” business model that was taking off in Silicon Valley

- the history of mutual funds moving from investing in publicly traded stocks to startups

- The effect of this influx of investment cash from mutual funds was to push already lofty startup valuations even higher

- Andy Boyd evaluated WeWork in 2014, he and an analyst on his team couldn’t make the math work at a $5 billion valuation. With their opinions unchanged this time around, the analyst even filed a memo detailing her many concerns with the company. Its revenue was tied to physical space—it looked like a real estate company, not a tech company, so the valuation was far too high

- The mutual fund deals also enabled Neumann to seize more control. Neumann’s votes got 10 votes per share

Chapter 10: Bubbling Over

- Mark Dixon, CEO of Regus, tried to figure out why WeWork had a higher valuation than Regus when their business model is pretty much identical

- Regus was featured in The Silicon Valley Magazine as the “office of the future” Dixon said “If we get it right, we have an opportunity to change to world”

- At a valuation of $10b, WeWork was worth $300k/member while Regus came out to roughly 10k/member. WeWork’s valuation was >50x its revenue for 2015

- Problems of WeWork

- From afar, the company’s business model looked exactly like Regus’s: leasing office space long term and subletting it short term. But surely WeWork must have been doing something different to merit its colossal valuation—something that tech investors understood but that wasn’t obvious to an outsider?

- Dixon and his team analysed WeWork and concluded that WeWork had a nearly identical biz model, they couldn’t find any clear differentiator beyond the hype and the “community” – obsessed marketing

- WeWork’s architecture was both inviting and efficient—it was able to pack far more desks into the same amount of space […] these advantages didn’t lead to profits. The energy and aesthetic of WeWork didn’t result in noticeably higher rents; instead, WeWork’s rents were comparable to Regus’s. While Facebook and LinkedIn benefited from a “network effect” where the bigger they got, the better they could serve targeted high-priced ads or charge more to recruiters, there was no real corollary for WeWork. As WeWork got bigger, so too did its costs

- Mutual fund managers and VCs were amazed by WeWork’s growth rate. The problem was that this was circular logic. If WeWork didn’t continue to raise more money at giant valuations, it would never have been able to keep up the pace. Instead, its business would have looked a lot like Regus’s—but for millennials.

- Dixon bought a small Dutch company called Spaces – a WeWork clone

- Like a tall flute of champagne, modern capitalism has long been full of bubbles that rise to the surface and pop.

- bubbles are the result of a herd of people who collectively start paying more for something than its intrinsic value

- In bubbles, the herd and its collective psychology prevail over the individual. Euphoria wins out over skepticism.

- Problems with the startup world in general – a delusion

- a lot of startups are unprofitable

- a massive wealth transfer was going on from venture capital funds spilling over with money to consumers who got below-cost products

- At a basic level, what was happening was the amount of money chasing companies had grown far faster than the number of good ideas

- investors valued growth over profitable biz, therefore startups chase revenue growth by selling goods under cost

- The startup-focused press in particular was more cheerleader than watchdog. The digital publication TechCrunch amplified narratives about how startups would disrupt X industry and reshape the world.

- With little skepticism from the media and elsewhere, tech investors began to pile money into an emerging class of companies that weren’t tech companies but acted the part.

- WeWork was a by-product of the same mass delusion that raised the valuations of “tech” companies higher and higher. Investors saw a physical social network with amazing growth rather than a collection of people paying market rents for office space that had losses growing just as fast as revenue. When Neumann told them WeWork was like Uber and Airbnb, the investors focused on the few parallels between those businesses rather than numerous fundamental differences, including how Airbnb and Uber are asset-light and don’t have costly fifteen-year leases for their homes and cars.

- Brandon Shorenstein knew WeWork was a bubble and it wasn’t going to end well

Chapter 11: Catnip for Millennials

- Scale-up WeWork more efficiently by using “building information modelling”

- The firm built software for WeWork to better plan projects and timelines, helping turn WeWork into a machine that could quickly spit out plans for new offices.

- Organisations take advantage of people’s desire for belonging and purpose

WeWork: making the world a better place

Facebook: make the world more open and connected

Airbnb: let people belong anywhere - WeWork’s official mission, which Rebekah Neumann had crafted, was to create a world “where people work to make a life, not just a living.”

- WeWork expanding into the residential sector by building WeLive

- As an economic venture, WeLive was effectively doomed from the start. One of the reasons WeWork’s main business was so appealing was its density. WeWork managed to get two or three times as many people on a floor than in a standard office design. […] Apartment buildings, though, can’t just absorb three times more people.

- Despite all the hype and lofty projections that helped win hundreds of millions of dollars from investors, WeLive never expanded beyond the two locations.

- Neumann sold his shares to investors for the same price Fidelity was valued – valuing the company at $10b. While the long-serving employees sold their shares back to WeWork with 25% less than Neumann.

Chapter 12: Banking Bros

- Hoping to win WeWorl’s IPO down the line, Jimmy Lee and Noah Wintroub helped arrange a huge credit line for WeWork, one that would eventually grow to give WeWork access to more than $500m in debt by 2015

Chapter 13: Taking Over the World

- Neumann was addicted to fund-raising. For him, the company’s valuation was a measuring stick for how he stacked up against the known names in Silicon Valley

- The startup bubble was about to burst

➊ Neumann wanted to raise at an increased valuation between 15-20b even tho WeWork had just months before raised at $5b then $10b.

➋ Nothing had changed about the business, why should its valuation go up past $15b now

➌ Bill Gurley “We are in a risk bubble.” - WeWork’s growth until that point was enabled above all by its ability to attract ever-larger sums. If the fundraising machine ever turned off, so, too, would WeWork’s growth, and with it its lofty valuation.

- In 2014, WeWork took in $74 million of revenue yet reported an operating loss of $88 million, its own records show. This came even though WeWork, just a few months before the end of 2014, told investors it expected an operating profit of $4.2 million. Into 2015, it veered further off its path of projected profits. Instead of the $49 million operating profit, it had predicted, it ended the year with a $227 million operating loss.

- By the end of the second weeklong trip, Goldman Sachs surveyed the funding landscape and found relatively little interest. Neumann had been aggressive in his pitches, making it clear that he expected a valuation above $15 billion, rather than the standard practice of playing coy on price.

PART III

Chapter 14: Friends in High Places

- Neumann speaking at Startup India

- Masayoshi Son has a fixation on making money

- Son wanted more than just his empire in Japan. he wanted to be in the orbit of Bill Gates and other tech magnates

- While Son could be a fierce negotiator, he was also developing a tendency to become so enraptured by an idea or a founder that he ended up paying a price far beyond what a seller might even think about. eg SoftBank paid $800m to acquire Comdex, Sheldon Adelson initially asked for $300m

Chapter 15: It’s Tricky

- Neuman likes to surf but not the paddling elements of the sport therefore WeWork got into the surfing business

- Wavegarden’s technology – a mechanical spine in the centre attached to a snowplough-like arm that pushed water into wave after wave.

- WeWork paid $13.8m in cash & stock for a 42% stake which the board approved the deal

- As WeWork poured money into questionable ventures like Wavegarden, the company was still struggling to make money in its main business of subleasing office space.

- WeWork was spending $2 for every $1 it took in and was losing $1m a day

- To prep for IPO, WeWork needed to improve its loose spending habits

- First, they fired 7% of its staff (~70 people)

Chapter 16: One Billion Dollars per Minute

- In 2016, Son wasn’t not getting where he wanted to be through buying companies and operating them. He decided to focus on investing

- He needed more money, not just his personal fund

- He’d need a leader to take a risk on them

- He believes “Life is too short to think small”

- He wanted to raise 100b but the biggest VC fund ever raised had been only around $3b

- Saudi Arabia – MBS’s vision 2030

- Saudi Arabic’ Public Investment Fund (IPO) wrote a $3.5b cheque to Uber

- Son said he could give MBS and the kingdom a $1T gift and put Saudi Arabia at the centre of the technology revolution by giving him $100b

- MBS gave him $45b in a 45mins meeting, “one billion dollars per minute”

Chapter 17: Neumann & Son

- Neumann meeting Son in one of the WeWork offices

- Son wanted to invest over $4b in WeWork

- Son invested in the people. His best bets had come as a result of the pure gut, and he was convinced that Neumann was something special.

- Son’s longtime deputy Nikesh Arora was well known to have strong resistance to WeWork. He had berated one of SoftBank’s fund managers when he first pitched WeWork as an investment, telling the fund manager he was an idiot for trying to say a real estate company with no profits could ever scale like a technology company.

- Son runs very hotly and cold, Schwartz warned them. He’s very hot on this right now, Schwartz said, but if he turns cold, it could be a problem for WeWork.

Chapter 18: Crazy Train

- A gift Neumann sent to Son for a $4.4B investment

- WeWork paid $50k to get it shipped to Japan. It was a telling sign of how Neumann and Son—with legions of staffers and piles of money at their disposal—were able to force the impossible into existence.

- The key to closing the deal was getting through SoftBank’s DD

- SoftBank’s DD Concern # 1: WeWork’s prior projections that forecast huge near-term profits, but it was clear that WeWork was instead experiencing larger and larger losses. The company had wildly missed its goals.

- Concern # 2: The mutual fund, T. Rowe Price gave the company a valuation of $12b not $16b

- None of the red flags matter. Once Son made a decision, his team was expected to execute the deal, not question it.

- The new $4.4b fund WeWork valuation would rise to $20b

➊ $3.1b – new money to WeWork to fund expansion

➋ $1.3b – buying stock from existing investors and employees - Son wanted Neumann to become more bold and rash

- Son introduced Neumann to Cheng Wei of Didi who was crazier than Travis Kalanick

- “In a fight, who wins?” The smart guy or the crazy guy? Being crazy is how you win. You’re not crazy enough.” Son told Neumann

Chapter 19: Revenue, Multiple, Valuation

- What WeWork was?

- As Neumann began spending heavily to build out a broader vision for WeWork, he never seemed to have a clear picture of what the company was, only what it wasn’t.

- Is WeWork a community company? or a tech company? or a real estate company?

- “We used to view ourselves as a community company, but we are starting to figure out now that we ourselves are still discovering what is the best type of company that we want to be,” he said, adding it was neither real estate nor tech.

- Neumann acquired 2 companies

➊ Meetup, an event planning website – WeWork to host Meetup events, and turn those participants into members

➋ Flatiron Schoo, a coding Bootcamp helped fill in the WeWork space - Neumann sent arrows in numerous directions

➊ Rise by We, a gym

➋ Interior design, helped Expedia redesign a small outpost in Chicago

➌ Elementary school, the concept was to raise “conscious global citizens” - Keeping up the pace of this growth was starting to get harder. Neumann wanted to keep doubling every year—a task that required an enormous amount of leasing and money.

- For its first locations, WeWork was able to find members through Craigslist and word of mouth. Then it added a constant stream of tech mixers and other events where WeWork drew in potential tenants and showed off its space. Then it leaned on referral bonuses, online ads, and calls to people based in a Regus office. It eventually started paying brokers commissions to bring in tenants.

- To get real estate brokers interested, it offered big promotions like 20% of the value of a lease—double the market rate paid by competitors like Regus.

- WeWork offered Industrious (their competitor), current tenants, to work at WeWork for free, a full year’s rent for free.

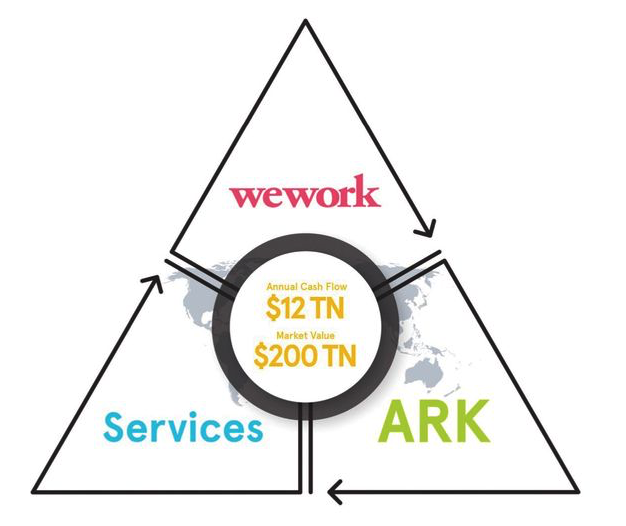

- “He would oftentimes do his napkin sketch on revenue, multiple, valuation,” one senior executive recalls. “He would say, we have to get to $10 billion in revenue, because we’ll get $200 billion in valuation.”

Chapter 20: Community-Adjusted Profit

- WeWork constantly needed money

- Artie Minson, the CFO, tried to raise funds using bonds —a form of debt that is traded almost like stock between investors. It would allow WeWork to borrow hundreds of millions of dollars without selling a slice of the company.

- When investors asked questions about losses, Minson often told them they didn’t get WeWork. The company lost money only because of its growth rate, he would say. If they simply stopped expansion or slowed it down, the company could become instantly profitable.

- Minson turned to a formula that they’d been showing to investors and in internal projections and infused it with WeWork branding: “community-adjusted EBITDA.”

- landlords typically gave the company the first year of free

- By normal measures, WeWork’s revenue doubled to $866m in 2017, and its losses more than doubled to $933m that year. But using Minson’s new definition, WeWork had actually generated $233m in profits.

- WeWork’s business model was a lot like the cable business. It cost a lot to string miles of cable on telephone poles and into people’s homes. But once customers signed up, the cable boxes in people’s homes eventually spewed money month after month. With community-adjusted EBITDA, Minson had found a way to distil the ethereal nature of WeWork’s profitability down to a formula that could be served up to Wall Street.

- Selling $702m of bonds

- Within a day of raising the debt, the price of WeWork’s bonds began to fall. They dropped to 97 cents on the dollar by the third day of trading and then to 94 over the next two weeks.

- They spent $32m to buy back a chunk of the very same financial instruments it sold.

Chapter 21: Adam’s ARK

- WeWork Property Investors – A private equity fund devoted to buying buildings where WeWork was leasing. Owned and run jointly by WeWork and Rhône Group. The business was a tangled knot of conflicts of interest

- ARK fund – Neumann wanted to create the largest real estate investment firm on the planet. He wanted to raise $100b

- Neumann had financial engineering plans of his own. In addition to the benefits he saw in the business, ARK offered a way for him to get an even more lucrative remuneration package

- Neumann was prioritizing his own wealth over WeWork; he wanted it personally.

Chapter 22: The $3 Trillion Triangle

- “We are unicorn hunters” Son

- Son often offered much more than the startup initially requested.

- The WeWork system: the triangle strategy. Each would be a $1T business on its own

- Neumann wanted to take on the entire real estate market

- Neumann wanted $70b to accomplish what he envisioned

- With SoftBank’s support, WeWork would be worth $10T by 2028

- The plan they were discussing was on a scale beyond the audacious, yet they seemed to view it with a sense of certainty

- Son would buy out all of Neumann’s existing investors for about $10b and put another $10b into WeWork, giving SoftBank ownership of most of the company while leaving Neumann as the only other large owner remaining. The valuation would equate to roughly $47b.

Chapter 23: Summer Camp

- WeWork summer camp had ballooned into a massive production

➊ part music festival

➋ part Burning Man

➌ part corporate development retreat—all caked in exuberant partying and cultlike self-adulation

Chapter 24: Shoes Off, Souls Inside

- WeGrow, WeWork’s private elementary school

- The Montessori teaching method espouses giving students “freedom within limits.” Rugs are particularly important because they outline spaces for students to sit together in morning circles and do their own work. Rebekah wanted to find the perfect rugs—all in white. For the first several months, while she continued to seek out the right white rugs, the teachers used masking tape to outline places for students to sit.

- Rebekah sought to intervene in so many areas

➊ On hiring

➋ Teacher’s salary like Why were teachers getting paid so much, and why did they want more? It’s an honour to be a part of this, she said. We don’t want staff who are just doing this for the money

➌ School curriculum. Rebekah’s ideas about the curriculum changed daily. She took to questioning the teachers on day-to-day decisions, often based on feedback from her children

Chapter 25: Flying High

- Neumann’s growing ego

- Neumann had been flying on a rented Bombardier Global Express

- Other corporations owned their own aircraft for executive travel. He wanted his own status symbol—a shiny beacon of extreme corporate wealth

- For most corporations, such transportation is hardly a rational choice. The cost difference between flying private and commercial is simply extraordinary, making it extremely hard to justify economically.

- Neumann’s partying up high

➊ booze flowed heavily. Shots came out quickly, as did pot.

➋ Passengers were spitting tequila on each other

➌ There was so much marijuana smoke in the cabin that the crew was forced to pull out the jet’s oxygen masks and put them on. - Neumann often enacted cost savings by demanding cuts to travel budgets other than his own, forcing some executives to fly coach on international trips. the rules don’t apply to Neumann

- Hazy vision & ambiguous credo: Neumann frequently references Bezo’s transformation of Amazon. Offices to us are like what books were to Bezos, he would say. But what was the other half of that analogy for WeWork? What was WeWork’s equivalent of developing the dominant global e-commerce platform?

- “We are here in order to change the world — nothing less than that interests me,”

- increasingly puzzling acquisitions & new lines of biz

➊ Conductor, a search optimisation startup — zero connection to WeWork’s core biz

➋ Cushman & Wakefield, a real estate brokerage

➌ Lyft – It would have been a rather strange marriage: two aging startups, both bleeding money, with one investing the VC dollars it raised from Softbank into the other - Through Neuman’s lens of valuation, such deals made sense. Cos Softbank was clearly valuing WeWork based on its revenue, no its losses.

- WeWork’s sprawling ambitions reflected its founder’s growing ego

➊ Neumann saw himself playing a bigger role in society

➋ It needed to have the biggest valuation

➌ His goal went from PM of Israel to the “President of the World” - He had one meeting with the Canadian prime minister, Justin Trudeau, and the prime minister’s office wanted him to come to Ottawa for another. WeWork was set to announce a planned expansion in Canada. They scheduled date, but less than a week before the event Neumann decided he needed to reschedule. The request was effectively a snub in the hierarchical world of politics; the prime minister of Canada shouldn’t have to rework his schedule around an indecisive CEO of an ambitious but decidedly midsized company. He never got another meeting.

- Neumann aspired to live forever

- Neumann wanted Isaacson to write a biography about him

- Prince Mohammed just needed better guidance, better advice, Neumann told Hadley. Who could offer such counsel? the veteran foreign affairs official wondered. Without hesitation, Neumann replied, “Me.”

Chapter 26: Both Mark and Sheryl

- In Silicon Valley, it had become conventional wisdom that a visionary founder should hire a business-focused right-hand operator to bring the business into shape.

➊ Facebook: Mark Zuckerberg + Sheryl Sandberg

➋ Google: Larry Page & Sergey Brin + Eric Schmidt

➌ WeWork: Neumann + Neumann - Neumann, struggling to delegate, wanted to be involved in a litany of decisions

- Nepotism is a common theme at WeWork

➊ Important roles throughout the organization were filled by friends and family

➋ Many people did not qualify for their jobs

➌ Executives were scared to speak up

➍ In a C-suite culture in which saying no or voicing criticism was implicitly discouraged

Chapter 27: Broken Fortitude

- SoftBank was slated to spend $10 billion to buy stock from employees and existing investors, it was set to be the largest ever investment in or buyout of a US startup

- WeWork was going to be worth roughly $10 billion on paper after the deal

- Two growth-addicted CEOs focused only on revenue, ignoring profitability

- The level of growth needed to hit $50 billion in revenue was almost inconceivable. It meant doubling revenue every year for the next five years. Such exponential growth might be manageable in the early years, but in a company of WeWork’s size, it was becoming an extraordinarily onerous lift.

- Neumann wanted assurances that he would stay in control—and unfettered grip, even though Son was putting up all the money. SoftBank, however, wanted clauses so it could remove him under certain circumstances—a reasonable ask.

- Neumann negotiated to the point where SoftBank wouldn’t be able to remove him—without paying a large penalty—if he went to jail on just any felony, for example.

- His lawyers pushed for a provision where he would have to commit a violent felony before SoftBank could remove him without penalty.

- Saudi Public Investment Fund (PIF) put in 45b in the vision fund. Son needed the principal funders’ approval on buying out WeWork for $20B. The math didn’t make sense for the Saudi team. Vision Fund pulled out of the deal

- Softbank put up its own money to close the deal cos Son believed “WeWork is the next Alibaba”

- SoftBank’s Japan telecom unit raised 24b in the IPO. Both SoftBank and the telecom unit’s stock prices continued to fall. Softbank team told Son the deal had to be called off

- Son explained to Neumann that SoftBank’s stock had gotten hit so hard by the sell-off in tech stocks that they didn’t have the money to pay for WeWork anymore. The deal was dead.

- Neumann reverted to a simple pitch that he hoped would play to Son’s insecurities: the fear of missing out. Son eventually agreed to invest an additional $2 billion in WeWork—$1 billion of new cash, $1 billion to buy out existing investors.

Part IV

Chapter 28: Diseconomies of Scale

- WeWork was bleeding cash. In 2018, spending $3.5b, revenue was just $1.8b

- Diseconomies of Scale in all departments across WeWork

- WeWork spent their money recklessly and inefficiently

- Neumann’s inclinations for new biz ventures often enmeshed with his personal interests continued unrestrained

Chapter 29: Guitar House

- Failed SoftBank deal seemed to haunt Neumann for months

- Neumann engaged with others to drum up new biz

- Apple – Neumann pitched Apple on the idea that a supercharged version of the WeWork key card could be tired into the iPhone

- Airbnb – WeWork & AirBnb world bulk 10k apartment units theywould rent on AirBnb. Neumann later came back with a new plan – building 10m apartments. It would have costsed them $1T

- Neumann wasn’t humbled by the deal’s collapse. Instead, having been abandoned at the altar by his mentor, his insecurity grew. And so did his ego

Chapter 30: The Plunge Before the Plunge

- WeWork needed to go public

- IPO is akin to an election campaign. An IPO isn’t a graduation ceremony for a company transitioning from the world of private investment to the public stock market. Companies truly must sell themselves to the public

- Bake-off

➊ Morgan Stanley: $25b ~ $60b

➋ Goldman Sachs: $61b ~ $96b

➌ JP Morgan: $46b ~ $63b - Goldman told WeWork it would charge $200 million in up-front fees just to make the $10b loans

- 6 months after the bake-off meetings, Goldman began to wave. Goldman told WeWork it would likely be able to guarantee only $3.65 billion of the debt, and it would work with other banks like JPMorgan to raise the rest.

- JP Morgan readied a plan to help WeWork borrow $6b. Unlike Goldman’s debt package, JPMorgan’s offer required that WeWork complete an IPO. WeWork would need to raise at least $3b from the stock market in order to get JPMorgan’s $6b in debt

- Neumann told the Goldman bankers why he was going with JPMorgan. It was a sure, safe bet. Dimon had personally promised that JPMorgan could get them $6 billion.

Chapter 31: To the Energy of We

- In spring 2019, the WeWork team was writing their IPO prospectus (S-1)

- 9 years into its existence, the company still didn’t have its story down

- There was no consensus on how to describe WeWork. If it wasn’t a real estate company, what was it? Neumann urged his team to draw upon one of the most overused terms in Silicon Valley—to show how WeWork was a “platform”—a descriptor that implied an online locus of connectivity with few assets, like Craigslist or Reddit. “We are a global physical platform,”

- WeWork was struggling to figure out how to even present its numbers

- JP Morgan & Goldman had a slide that implied WeWork would have a $30b valuation — a sharp pullback from the far rosier projections and a sharp drop from the $47b mark from SoftBank in Jan

Chapter 32: Twenty to One

- Neumann’s plan to double the potency of his already supercharged shares to give them 20x the votes of a standard investor

- It gave him the ability to sell billions of dollars worth of his own stock while still wielding full control

- He didn’t learn his lesson from the 2018 Softbank deal, he asked too much that the deal ended up falling apart

- Neumann’s personal loan tied to WeWork

➊ Banks wanted to get WeWork IPO deals, they lined up to off Neumann personal loans

➋ They let him personally borrow up to $500m, and would get WeWork stock if he couldn’t pay it back

➌ Neumann had drawn $380m

➍ Such borrowing would affect CEO’s decisions - Neumann and McKelvey profiting off the We trademark. WeWork had purchased the rights to trademarks relating to the word “We” from We Holdings LLC, Neumann’s LLC, paying the entity $5.9m in stock

Chapter 33: WeWTF: The S-1 Sh*T Show

- The overall response from the public was bad

- Scott Galloway – WeWTF

- The banker began to lower WeWork’s valuation from $96b to less than $30b.

- It made it harder for them to raise money cos JP Morgan structured its debt deal based on the IPO valuation

Chapter 34: A Setting Son

- Son’s wanted to do a second fund

- Son told Neumann to call off the IPO and threaten to use his influence to block the IPO if Neumann pushed ahead

- A bad WeWork IPO was going to destroy the second Vision Fund

Chapter 36: The Fall of Adam

- Mary Erdoes: Maybe it would be best for WeWork if you aren’t the CEO

- For almost a decade, Neumann’s backers thought he could do no wrong. He had shifted people’s perception of reality, persuading one after another of the world’s top investors to come along for the ride, boosting WeWork’s valuation and pumping the company with more money every time.

- It didn’t matter that Neumann publicly said WeWork was profitable when it wasn’t or that he took out hundreds of millions of dollars to spend on homes and staff that trailed him around; it didn’t matter that WeWork was spending $2 for every $1 it took in; it didn’t matter that WeWork was a real estate company. None of it mattered because Neumann was able to convince the market that WeWork had extraordinary value—that its future as a ubiquitous world-changing corporation was inevitable.

- Now, though, his magic was gone. He was no longer a visionary able to move mountains. He was a meme—a caricature of an irresponsible CEO, driven by avarice and narcissism. Now that the public market investors had made clear they didn’t think WeWork was even a $15 billion or $20 billion company, it was obvious the billions on paper had vanished. Neumann’s power—his invincibility—plunged with it.

Chapter 37: DeNeumannization

- If WeWork wasn’t a $47b tech company, what was it?

- Neumann’s fall had an impact far outside of WeWork’s offices. The dominant thesis of the era—that giant losses didn’t matter so long as companies had big vision and revenue growth—suddenly looked naïve. The public markets, it turned out, wanted real businesses, not dreams.

- Son began to pivot. As WeWork was flailing, SoftBank executives instructed many of the companies they funded to do the opposite of everything they had preached. They should be focused on getting to profitability and even consider layoffs if necessary.

- SoftBank officials were no longer implying that fast-growing companies, particularly those with big losses, should expect more funding. While this missive was mostly likely insulting and frustrating to the CEOs who accepted SoftBank’s money, it didn’t make much sense. If getting to profits was the focus, what was the point of all the money SoftBank gave them? Spending money, by definition, tends to mean larger up-front losses.

- The various sovereign wealth funds, hedge funds, and pension plans Son was trying to round up immediately began to question his judgment, particularly given how obvious WeWork’s warning signs looked in hindsight. If he thought WeWork was a $47 billion tech company, why would investors trust him with even more billions?

Chapter 38: Bread of Shame

- “We’re going to run out of money.”

- WeWork was broke. It was burning cash at an astounding rate and was on track to run out of money in less than two months, more than five months faster than even cynical analysts had projected. The cash crunch was so severe that they couldn’t even afford layoffs. They realized they didn’t have enough money to pay the severance costs associated with the thousands of job cuts they planned.

- A host of SoftBank employees camped out in WeWork’s headquarters, which irked WeWork executives, especially Minson. The company gave us $10 billion, and now they’re asking basic questions about the company’s finances? Shouldn’t they have done that earlier?

- Now the potential debt investors got to see a key figure that was never included in WeWork’s IPO prospectus: the profit margins of mature locations that had been open for two years. Unlike community-adjusted EBITDA, mature location margins are a standard indicator in the industry that shows how many average buildings generate profit, excluding costs at headquarters.

- SoftBank was valuing WeWork at roughly $8 billion. Down from $47 billion ten months earlier

- Neumann needed money from SoftBank

➊ a new loan + a giant payment of cash to go away

➋ SoftBank would give him a new loan to repay his $500 million in debt, and he could sell roughly $1 billion of his shares alongside employees and other investors. The conglomerate even assented to Neumann’s request to forgive his debts to WeWork—the roughly $1.7 million he owed the company for all his personal private jet trips and other expenses from recent months.

➌ Claure agreed that SoftBank would pay Neumann money structured as a consulting fee, one that would come in as a few separate payments over time.

➍ The amount: $185 million. - Board members quietly expressed disgust to each other at the size and the terms of Neumann’s payout. Neumann’s avarice and antics had made the company so toxic it couldn’t go public. Now he’d be walking away with over $1.1 billion in cash and a new $500 million loan. It was an enormous haul for a now-disgraced former CEO.

- The bread of shame: According to the Kabbalistic maxim, the bread tastes good only if it’s earned through hard work. Otherwise, it has a bitter taste “If the person you are looking to share with doesn’t want to make an effort and is just looking for a ‘handout,’ it is a case of Bread of Shame,” Michael Berg

- The Neumanns had their own bread of shame

➊ Neumann was leaving extraordinarily rich

➋ He was getting paid to walk away from the mess he created. - The cries of revulsion and anger from within WeWork came swiftly and loudly. The valuation had fallen so much that their options were underwater, meaning they were effectively worthless. Pouring acid into the wound was Neumann’s payout. While most of the staff got years of promises of riches and now had nothing, Neumann was getting a $185 million payout to not be CEO of his company anymore, on top of the $1 billion in stock he could sell.

- Lessons for Masayoshi Son

➊ Investors weren’t taking him up on his second Vision Fund

➋ The $108 billion in commitments he thought he once had proved illusory; no one was signing

➌ The aura of the founder—the idea that visionaries should be blindly followed so long as they had charisma and charm and spoke the right startup lingo—had begun to wear off

➍ the traditional rules of business, where profits matter, still applied.

Buy on Amazon

◃ Back